Thinking, Fast and Slow

Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman is dense and introduces you to foundational ideas in behavioral science. It’s shocking, entertaining, and probably more educational than any college course I’ve taken. It introduces you to the fallibility of your own brain in quite a delightful way.

The following summary does no justice to the book — I wrote it primarily for myself so that I can quickly brush up on these ideas once in a while. You really have to read the book itself to truly appreciate the beauty in how clueless our brains are.

Part I: Two Systems

Our brains can be thought of as two systems working together: let’s call them System 1 and System 2. System 1 is your fast thinking, automatic, intuitive, subconscious part of the brain. System 2 is the slow thinking, deliberate, effortful, logical, conscious part of the brain.

It’s System 1 that effortlessly tells you what 2+2 is, while it’s System 2 that has to step in when you are asked the answer to 17 x 24. System 1 uses association and metaphor to quickly bubble up an answer to our head. And although that answer is usually correct and useful — illusions, both visual and cognitive, are a result of System 1 producing a wrong one. To make matters worse, System 2 is lazy and doesn’t step in unless called for, requires attention and effort and gets tired easily.

The goal of this book is to recognize the systematic errors that System 1 makes and avoid them, especially when the stakes are high. Next, I’ll try to list down all the major heuristics discussed in the book.

Part II: Heuristics and Biases

- What You See Is All There Is (WYSIATI): Our System 1 only works on activated ideas. Information that is not retreived by this associative machine (even unconsciously) from memory might as well not exist.

- Priming: Exposure to an idea triggers the System 1’s associative machine and primes us to think about related ideas.

- Cognitive Ease: Things that are more familiar or easier to comprehend seem to be more true than things that are novel or require hard thought. If we hear a lie often enough, we tend to believe it.

- Coherent Stories: We are more likely to believe something if it’s easy to fit into a coherent story. We confuse causality with correlation and make more out of coincidence than is statistically warranted.

- Confirmation Bias: We tend to search for and find confirming evidence for a belief while overlooking counter-examples.

- Halo Effect: We tend to like or dislike everything about someone else — even the things we haven’t observed.

- Substitution: We substitute a hard question with an easier one. When asked about how happy we are with our life, we answer the question “What is my mood right now?”

- The Law of Small Numbers: Small samples are more prone to extreme outcomes than large ones, but we tend to lend the outcomes of small samples more credence than statistically warranted.

- Overconfidence: We tend to suppress ambiguity and doubt by constructing coherent stories from scraps of data. One way to make better decisions is to just be less confident.

- Anchoring Effect: Making incorrect estimates due to previously heard numbers, even if those numbers don’t have anything to do with the estimate you’re trying to arrive at.

- Availability Heuristic and Cascades: We rely on immediate examples that come to our mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method or decision. We over react to a minor problem simply because we hear a disproportionate number of negative news stories than positive ones. A recent plane crash makes us think air travel is more dangerous than car travel.

- Representativeness: We make judgements based on profiling or stereotyping, instead of probability, base rate or sampling sizes.

- Conjugation Fallacy: We choose a plausibe story over a probably story. Consider the Linda Experiment: Linda is single, outspoken and very bright, and as a student, was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice. Which is more probable? (1) Linda is a bank teller, or (2) Linda is a bank teller active in the feminist movement. The correct answer is (1), and don’t feel too bad if you got it wrong since 85% of Stanford’s Graduate School of Business students also flunked this test. Statistically, there are fewer feminist female bank tellers than female bank tellers.

- Overlooking Statistics: Given statistical data and an individual story, we tend to attach more value to the story than the data.

- Overlooking Luck: Tendency to attach causal interpretations to fluctuations of random processes. When we remove these causal stories and consider mere statistics, we observe regularities like regression to the mean.

Part III: Overconfidence

- The Narrative Fallacy: We create flawed explanatory stories of the past that shape our views of the world and expectations of the future.

- The Hindsight Illusion: Our intuitions and premonitions feel more true after the fact. Hindsight is 20/20.

- The Illusion of Validity: We cling with confidence to our opinions, predictions and points of view even in the face of counter-evidence. Confidence is not a measure of accuracy.

- Ignoring Formulas: We overlook statistical information and favor intuition over formulas. Always rely on algorithms for important decisions when available over your subjective feelings, hunches, or intuition.

- Trusting Expert Intuition: Trust experts when the environment is sufficiently regular so as to be predictable, and the expert has learned these regularities through prolonged exposure.

- The Planning Fallacy: We take on risky projects with the best case scenario in mind, without considering the outside view of others who have engaged in similar projects in the past. A good way around this fallacy is to do a pre-mortem: before you start, think of all the ways your project can fail.

- The Optimistic Bias: We believe that we are at a lesser risk of experiencing a negative event compared to others. A way to make better decisions to be less optimistic.

- Theory-Induced Blindness: Once we have accepted a theory and used it as a tool in our thinking, it is extraordinarily difficult to notice its flaws. If we come upon an observation that does not seem to fit the model, we assume that there must be a perfectly good explanation that we are somehow missing.

- Endowment Effect: An object we own and use is a lot more valuable than an object we don’t own and use.

Part IV: Choices

- Omitting Subjectivity: Bernoulli proposed money had fixed utility. But he failed to consider a person’s reference point. A million dollars is worth a lot to a poor person, but nothing to a billionaire.

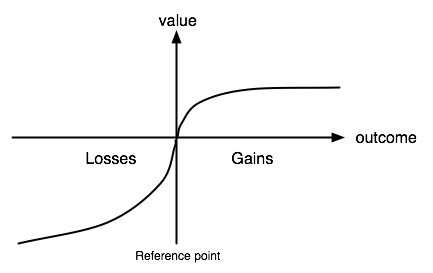

- Loss aversion: We dislike losing more than we like winning. A loss of $100 is worse than a gain of $100.

- Prospect Theory: Kahneman won the Nobel prize in economics by proposing Prospect Theory alongside Amos Tversky. It improves upon Bernoulli’s Utility Theory by accounting for loss aversion (greater slope on the loss side) and also for a subjective reference point.

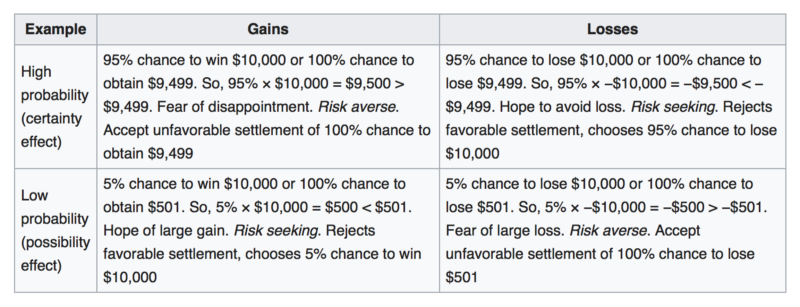

- Possibility Effect, Certainty Effect and the Fourfold Pattern:

- The Expectation Principle: As per the last two heuristics, we can see that the decision weights that we assign to outcomes are not identical to the probabilities of these outcomes. We contradict the Expectation Principle.

- Overestimating the likelihood of Rare Events: We choose the alternative in a decision which is described with explicit vividness, repetition and higher relative frequency. Availability Cascade and Cognitive Ease play a huge role in this.

- Thinking Narrowly: We are so risk averse that we avoid all gambles, even thought some gambles are on our side and by avoiding them we lose money.

- The Disposition Effect: We tend to sell stocks whose price has increased, while keeping ones that have dropped in value.

- The Sunk Cost Fallacy: We continue to increase investment in a decision based on the cumulative prior investment (the sunk cost) despite new contradictory evidence.

- Fear of Regret: We avoid making decisions that lead to regret, without realizing how intensely those feeling of regret will be. It hurts less than we think.

- Ignoring Joint Evaluations: Joint evaluations highlight a feature that was not noticeable in single evaluations but is recognized as a decisive when detected. Who deserves more compensation? A person robbed in their local grocery store, or a person robbed in a store they almost never visit. In a joint evaluation, we can see that the location should have no effect on the compensation, but not so much when we consider the two cases individually.

- Framing Effect: We react to a particular choice in different ways depending on how it is presented.

Part V: The Two Selves

- Our Two Selves: We have an an Experiencing Self and a Remembering Self. The latter trumps the former.

- The Peak End Rule: We value an experience by its peak and how it ended.

- Duration Neglect: The duration of an experinece doesn’t seem as important as the memory of the experience.

- Affective Forecasting: Forecasting our own happiness in the future. We are particularly bad at this. Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert delves deeper into this.

- Focusing Illusion: When we’re asked to evaluate a decision, life satisfaction, or preference we err if we focus on only one thing.

This is #4 in a series of book reviews published weekly on this site.