Slack: Getting Past Burnout, Busywork, and the Myth of Total Efficiency

I finished reading Slack by Tom DeMarco this weekend — it's a quick short read with one main idea at its core: within organizations, efficiency and flexibility are unfortunately tied together in a tradeoff: as organizations get more efficient and get rid of slack, they lose their ability to change and reinvent themselves.

Since I read this one on a Kindle, I can share my top highlights from the book:

-

Slack is the time when reinvention happens. It is time when you are not 100 percent busy doing the operational business of your firm. Slack is the time when you are 0 percent busy.

-

The waste associated with time-sharing between two tasks is the sum of time lost to the mechanics of the switch plus rework required upon restart plus immersion time plus frustration cost. You pay the penalty each time you switch.

-

Knowledge workers aren’t fungible. Treating them as if they were will increase busyness but make it harder for them to get useful work done.

-

My short list of the benefits that come with sensibly designed-in slack includes all of the following:

- Flexibility, a capacity for ongoing organizational redesign

- Better people retention

- A capacity to invest

-

Slack is the way you invest in change. Slack represents operational capacity sacrificed in the interests of long-term health.

-

Companies within a single industry often have variations of turnover rate of as much as three or four times. A common feature of exit interviews is a sense that the departing person felt used. This leads to a disturbing paradox: The more successful a company is in extracting every bit of capacity from its workers, the more it exposes itself to turnover and attendant human capital loss.

-

It makes a lot of sense to invest in someone else when you have already saturated or nearly saturated your market. I am much more concerned, though, when smaller companies invest outside their own product areas. I see this as bankruptcy of inventiveness.

-

Slack is a kind of investment. Learning to think of it that way (instead of as waste) is what distinguishes organizations that are “in business” from those that are merely busy.

Aggressive Scheduling

- Managers apply pressure to their subordinates in a number of different ways, some of them obvious and some not. They do this, for example,

- by Turning the screws on delivery dates (aggressive scheduling)

- Loading on extra work

- Encouraging overtime

- Getting angry when disappointed

- Noting one subordinate’s extraordinary effort and praising it in the presence of the others.

- Being severe about anything other than superb performance

- Expecting great things of all your workers

- Railing against any apparent waste of time

- Setting an example yourself (with the boss laboring so mightily, there is certainly no time for anybody else to goof off)

- Creating incentives to encourage desired behavior or results

“People under time pressure don’t think faster.” —Tim Lister

-

Think rate is fixed. No matter what you do, no matter how hard you try, you can’t pick up the pace of thinking.

-

Since they can’t alter the rate of mental discriminations (basic elements of knowledge work) per second, their potential to respond to pressure is severely limited. All they can do is

- Eliminate wasted time

- Defer tasks that are not on the critical path

- Stay late

-

There just isn’t enough time in the day, and besides, the increasing pressures from family and personal life will soon tend to right the balance.

-

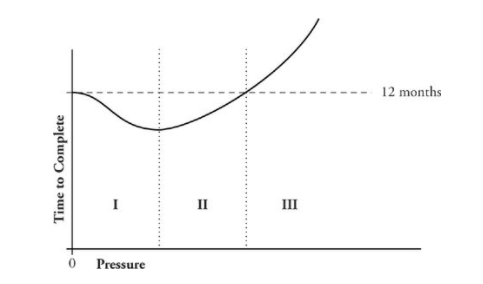

A more realistic model of how pressure impacts performance is shown in the graph below.

-

Here we see that pressure has a fairly limited capacity to reduce delivery time, maybe 10 or 15 percent at the most. And excessive pressure can quickly begin to worsen performance. The model is divided into three regions.

- In Region I, workers are responding to increased pressure by trimming any remaining waste, by concentrating on the critical path, and by staying late.

- In Region II, workers are getting tired, feeling pressure from home, and starting to put in a little “undertime” (taking the kid to the dentist during work hours, since the company owes them so much time anyway).

- In Region III, workers are polishing up their résumés and beginning to look for work elsewhere.

-

It’s the stressed-out organization that elevates the use of pressure to its prominent status. It makes its managers apply far too much. The long-term effect of too much pressure is demotivation, burnout, and loss of key people. The best managers use pressure only rarely and never over extended periods.

In my experience, projects in which the schedule is commonly termed aggressive or highly aggressive invariably turn out to be fiascoes.

-

“Aggressive schedule,” I’ve come to suspect, is a kind of code phrase—understood implicitly by all involved—for a schedule that is absurd, that has no chance at all of being met.

-

Managers during the commitment process can be like little boys posturing before a schoolyard fight: “I’m gonna knock your block off.” “I’m gonna wipe up the floor with you.” “I’m gonna hit you so hard your teeth will rattle.” This posturing is inconsistent with the desultory performance of the fight that follows (if there even is one), and even further removed from the demonstrated performance of fights past. So, too, the over-committing manager. He/she promises a level of performance not achieved in the past and not likely to be achieved in the future.

-

Overcommitment is not just an accident. Companies sometimes take purposeful steps to build an overcommitment ethic into their managers and into the corporate culture.

-

There is such a thing as a bad schedule. A bad schedule is one that sets a date that is subsequently missed. That’s it. That’s the beginning and the end of how a schedule should be judged. If the date is missed, the schedule was wrong. It doesn’t matter why the date was missed. The purpose of the schedule was planning, not goal-setting.

-

The missed schedule indicts the planners, not the workers. Even if the workers are utterly incompetent, a plan that takes careful note of their inadequacies can help to minimize the damage. A plan that takes no account of realities is not just useless but dangerous.

-

The people who set the schedule, not just the ones who failed to meet it, need to be held accountable.

Overtime

-

The decision to work overtime or to encourage others to do so is to override a fundamental design decision, one of the intrinsics of the enterprise. It is to say that that decision was wrong in the first place, that seven and a half hours, for example, was simply too little. It is the assertion that altering the deal to extract ten or eleven or twelve hours per day for the same pay will be to the organization’s real advantage.

-

When companies institute overtime, it’s not minutes per day they’re looking for. They increase the workday by huge increments, typically 40 or 50 percent. And they almost never have the courage to institutionalize this decision by redefining the official workday. I think they’re kidding themselves.

-

There is a useful distinction to make here between infrequent short bursts of overtime—what I call sprinting—and extended overtime. The manager who makes effective use of the occasional sprint is a hero. He/she needs impeccable timing, a flawless sense of what can and can’t be accomplished over a short period (there is no benefit if the delivery doesn’t take place on Monday or if it gets rejected), and enough raw leadership talent to pull the whole affair together. Finally, such a manager also needs to have a huge reserve of trust to dip into, the clear sense shared by all that the call for extraordinary effort is truly extraordinary, not likely to be wasted and not likely to become a regular fixture.

-

The “long into the night” example is perhaps too extreme. A more typical overtime regime is something like this: ten- or eleven-hour days Monday through Friday plus significant weekend time, all of it amounting to sixty-plus hours for the week. In this scheme, you may get a full night’s sleep every night. It’s your personal life that pays the price for the extra time given to the company.

-

Extended overtime is a productivity-reduction technique. It reduces the effect of each hour worked.

-

The best predictor of how much work a knowledge worker will accomplish is not the hours that he or she spends, but the days. The twelve-hour days don’t accomplish any more than the eight-hour days. Overtime is a wash.

-

There are four reasons why overtime hurts enough to offset the effect of the added hours. These are the invariable side effects of extended overtime:

- Reduced quality

- Personnel burnout

- Increased turnover of staff

- Ineffective use of time during normal hours

-

Most knowledge workers, for example, will tell you that they really shouldn’t do any kind of error-prone work late in a work session, because they know their thinking is no longer sufficiently clear for that kind of task.

-

Overindulgence in work, like overindulgence in anything else, will eventually lead to burnout.

-

Burned-out workers have no heart for anything—not for more overtime, not even for putting in a sensible eight hours a day.

-

In my reviews of overstressed projects, I am constantly amazed at the presence of so many zombies on the staff, people who go through the paces but no longer contribute. And they are often the ex-stars of the enterprise.

-

The first three hidden costs of extended overtime are dwarfed by the fourth, a tendency to waste normal workday hours in companies that are working a lot of overtime. When people are putting in thirty or forty hours a week of overtime, the basic hygienic acts of management to reduce daytime waste are for some reason suspended.

-

The oversize-meeting culture was made possible only because people were putting in so many extra hours to get work done. When we trimmed overtime, the first step toward sanity was assured. They had to cut way back on meetings and trim the population of each necessary meeting back to those people who were required to make whatever decision had justified the meeting in the first place.

-

Meetings are only one of the ways that overtime organizations waste the time of their most essential human resources. Another is that workers tend to drop their interrupt discipline during daylight hours. Knowing that their peers will be working long into the night, they feel free to interrupt them willy-nilly during “normal” work hours.

-

The poor worker who is there at midnight has probably stayed at his or her desk after regular closing just in the hope of having some peace and quiet for a little real work. What a shame that the organization can’t give such workers a decently interrupt-and noise-free environment during standard hours.

-

When overtime is the norm for workers, their managers tend to become pure workaholics. They run through their days, skip lunch, and put in far too many hours. When managers are overworked, they’re doing something other than management; the more they allow themselves to be overworked, the less real management gets done.

-

Workers who have been assured that their managers are deeply cognizant of their overtime hours may be unaware that the productivity figures used to measure those same managers leave out the overtime hours entirely.

-

This leads to an unfortunate management dynamic: Reported productivity can apparently be inflated by goading workers into working overtime; managers who extract more overtime from their workers look like more effective managers.

-

When people put in lots of overtime over an extended period of time, their net effectiveness is not just decreased during the extra hours; they begin to limp during the main body of the workday as well, due to built-up fatigue and reduced motivation.

Bad Management

First Law of Bad Management: If something isn’t working, do more of it. Second Law of Bad Management: Put yourself in as your own utility infielder.

-

All the rest of your people are busy as hell; you don’t want to further burden them with another task, particularly not one that upper management found to be of so little importance that they “trimmed ” the person who was doing it. Yet that “whatever” still has to be done. Oh well, you add it to your own burden and do it yourself.

-

I have known managers who took on as many as three full jobs reporting to their own management position.

-

Why do managers need to be told that management matters? At least in the United States and western Europe, there is a strange lore about management that in spite of the substantial salaries paid for it, it really isn’t essential to the proper running of the organization. In fact, the lore tells us, management is often in the way.

-

We also assign ourselves to lower-level work because we’re fleeing from challenge. The challenges of management are daunting: They lead us into the scarily intangible world of people relations, motivation, societal formation, conflict, and conflict resolution.

-

But management is all nuance. Why on earth is Maria so irritable? What’s the tension between Armand and Elwood? Is Danny looking for a new job, and what will we do if he leaves? Have I sold the due date as difficult but doable, or is everybody giggling at my naïveté? Did I hit the right tone in my briefing? Is my boss suddenly out of favor, and what does that mean to me?

-

Management is hard, and not because there is so much work to do (an overworked manager is almost certainly doing work he/she shouldn’t be doing). Management is hard because the skills are inherently difficult to master. Your mastery of them will affect your organization more than anything going on under you. Running away from the challenge doesn’t help.

-

Angry managers are losers, hapless incompetents who are in way over their heads and haven’t got the faintest idea how to lead.

The Culture of Fear

-

Once established, the Culture of Fear gets in the way of everything that is healthy or worthwhile. Growth is stunted, change (improvement) becomes nearly impossible, morale is in the Dumpster. Meaningful achievement is always just out of reach. Good people leave and new good people stay away in droves.

-

It’s tempting to say that overstressed organizations are always understaffed; that that’s where all the stress comes from in the first place. It’s tempting, but it isn’t entirely so. Meeting the deadline is not what this is all about. What this is about is looking like you’re trying your damnedest to meet the deadline.

-

In my experience, there are two important reasons why litigation happens in spite of the most dismal prospects for it ever achieving anything worthwhile:

- Litigation can be an effective way to deflect blame.

- Litigation can be a consequence of an intrinsically flawed contract.

-

At Microsoft, for example, there has long been an almost official policy of “sink, then swim.” People are loaded down with so much responsibility that they sink (fail). Then they have a chance to rest up, to analyze and modify their own performance.

-

Finding your weaknesses by failing is not just incidental; it is designed into the corporate philosophy.

-

The chemistry of Culture of Fear organizations seems to call for a fixed minimum amount of blame. In some companies, this minimum may even be written into policy. Consider, for example, G.E.’s policy that all managers be evaluated every year and the bottom 10 percent be fired.

-

Many of the contracts that eventually end up in litigation are so hopelessly flawed that neither party should ever have signed them. The most common flaw of these contracts is an unrealistic price and/or schedule.

-

A good contract requires slack. If a vendor commits to × by a given date, you act to your own peril to accept that commitment unless you can see that the vendor has left itself sufficient slack. If there are two competing vendors with different prices and the difference is explained by the fact that the cheaper one has cut all slack, then you court the disaster of litigation by choosing the low bidder. Similarly, if you are bidder, you need to know there is sufficient slack in the contract terms to cover reasonably expected risks.

Taylorism

-

Standards are not just good; they are essential to our modern way of life. Taylorism called for rigorous standardization of manual factory activity so that the human pieces of the process would be as interchangeable as the parts of the products. With nearly a century under its belt, Taylorism is still alive and well in the manufacturing sector today. I shall argue below that it is particularly ill suited to knowledge work, but there is no question that it is in common use in today’s factories.

-

Knowledge work is a domain for which Taylorism was never intended.

-

To establish a standardized way of doing any knowledge task, you end up focusing on the mechanics of the task. But the mechanics are a small and typically not very important portion of the whole. How the work goes on inside the nodes of the worker diagram is not nearly so important as how wide and rich are the connections.

-

That is the paradox of automation: It makes the work harder, not easier.

-

Process standards can be a highly emotional matter. There are “process wars,” as people begin to feel territorial about their vanishing prerogatives. After a new standard process has been installed, there may be blood in the corridors, a residue of bad feeling all around.

-

Process standardization from on high is disempowerment. It is a direct result of fearful management, allergic to failure.

-

But armor always has a side effect of reduced mobility. The overarmored organization has lost the ability to move and move quickly. When this happens, standard process is the cause of lost mobility. It is, however, not the root cause. The root cause is fear.

Quality

-

My problem with the Quality Movement is not that it costs too much or that it saps too much energy out of our organizations. My problem is that it is too little service and too much lip service.

-

But real quality is far more a matter of what it does for you and how it changes you than whether it is perfectly free of flaws. So that browser, even though it crashes maddeningly often, should be considered a quality product. That’s why you use it so much. Its quality is most of all a function of its usefulness.

-

Quality takes time. Even quality in the “defects only” sense takes time. So you might assume that a Quality Program for a development effort would, as its most important task, assure the quality of the schedule. I always assumed that. But so far, I have never come across a corporate Quality Program or a Quality Assurance organization that made any pretense of judging reasonableness of the time allocated for the work.

-

This relationship suggests a daring strategy for quality improvement: reduce quantity. Cutting out the inconsequential would be, for most of them, the most important act of quality improvement.

-

Quality takes time and reduces quantity, so it makes you, in a sense, less efficient.

-

You’re efficient when you do something with minimum waste. And you’re effective when you’re doing the right something.

-

The difference between strategic thinking and drift is a matter of whether the key choices are made mindfully or mindlessly. The idea that drift is often substituted for strategic direction-setting is no more surprising than the observation that visionary, charismatic leaders are few and far between.

-

Directing an entire organization is hard. Seeming to direct it, on the other hand, is easy. All you have to do is note which way the drift is moving and instruct the organization to go that way.

-

In addition to being flat-out hard to do, building effectiveness into an organization often comes into direct conflict with increasing efficiency.

Fisher’s fundamental theorem: “The more highly adapted an organism becomes, the less adaptable it is to any new change.”

- The more optimized an organism (organization) is, the more likely that the slack necessary to help it become more effective has been eliminated.

Management by Objectives

-

What on earth would cause them to favor efficient over effective? I’ll tell you. It’s a management philosophy called Management by Objectives. MBO companies respond to each failed quarter by instituting still more MBO. Bottom-line failures are excused as due to uncontrollable market factors, while successive improvements in selected quantitatively expressed objectives are loudly touted as proof that management really is succeeding in spite of the dismal results.

-

MBO is always based on stasis, the organization’s present steady state. MBO sends the message “Do everything the same as last year, only this year do more of X.”

-

The second flawed assumption of MBO is that the net contribution of something as large and complex as a corporate department can be reasonably approximated by a single indicator (or, in a more advanced MBO company, by two or three such indicators).

-

MBO is to an organization what Soviet-style central planning is to an economy: an idea whose time has passed.

Making organizational change

-

Part Three of the book turns to the subject of making organizational change—and hence growth—possible. This ambitious task involves more than simply removing barriers to change. It also requires vision, leadership, timing, and a lot more.

-

Slack is the lubricant that makes all these things possible. Vision and leadership, in particular, depend on degrees of freedom made available to the potential visionary or leader. Box these gifted people in tightly enough, and none of their magic will be able to happen.

-

It’s nontrivial for a company and everyone in it to know “who we are.” A little bit easier, however, is to know “who we aren’t.” When even that knowledge is missing—when there is no basis in the company to say about a given cockamamy scheme “it just isn’t us”—the company clearly lacks vision.

-

Like the human creature that fights wildly to resist changing whatever it considers its identity, the corporate organism without vision will hold on to stasis as its only meaningful definition of self.

-

The successful visionary statement will typically have the following characteristics:

- There has to be an element of present truth to the assertion. The challenge “Run a four-minute mile because that’s what we are all about ” would not inspire most of us because we wouldn’t see the present truth of the “what we’re all about” part.

- There is always an element of proposed future truth in the statement. Though it masquerades as “what we are all about, ” it is at least partly urging us toward “what we could be all about.”

- When the statement walks perfectly between what is and what could be, and the could-be part is wonderful but not impossible, acceptance by those listening is almost assured.

-

Leadership is the ability to enroll other people in your agenda. There is no easy formula for real leadership (if there were, we’d see a lot more of it), but it seems clear that the following elements always need to be present:

- Clear articulation of a direction

- Frank admission of the short-term pain

- Follow-up Follow-up Follow-up

-

Lack of power is a great excuse for failure, but sufficient power is never a necessary condition of leadership. There is never sufficient power. In fact, it is success in the absence of sufficient power that defines leadership.

-

It’s enrolling someone who is distinctly outside the scope of your official power base that constitutes real leadership.

-

It’s easy (and fair) to blame lousy management on lousy managers. But it’s not enough. It’s also necessary to blame the people who allow themselves to be managed so badly.

-

If you want to make change in your organization utterly impossible, try mocking people as they struggle with the new, unfamiliar ways you have just urged upon them. There is no surer way to stop essential change dead.

-

Without this gaining of trust, there is no leader, and no real turnaround. But how is trust gained, and how does it ever happen so swiftly? Just how are you supposed to demonstrate trustworthiness without having something entrusted to you to demonstrate upon? Whatever that something is, it has to be entrusted to you beforehand, and therefore well before you really deserve it. The truth is that there is no possibility of achieving trustworthiness except through the mechanism of undeserved trust.

-

More interesting, therefore, are the mechanics of acquiring not-yet-deserved trust. Here I see one pattern common to all the winners. The one mechanical practice they all have in common is this: They acquire trust by giving trust.

-

The giving of trust is an enormously powerful gesture. The recipient gives back loyalty as an almost autonomous response.

-

Growth is the rising tide that floats all boats. The period of growth is one in which people are naturally less change-resistant. It is therefore the optimal time to introduce any change.

Change happens in the middle management

-

An easy (but wrong) answer is that change happens at the top. The incentive for change may well come from the very top, but not the specifics of change. Change, particularly a significant one, involves reinvention. And corporate reinvention requires a deep involvement in the day-to-day business of the organization, something that top management is no longer likely to have. An equally wrong answer is that change happens at the bottom. People at the bottom of the hierarchy just don’t have the perspective to reinvent, nor do they have the power to carry out any reinvention scheme. If reinvention doesn’t happen at the top and it doesn’t happen at the bottom, there is only one possibility remaining: It’s got to happen in the middle.

-

Even companies that didn’t fire their change centers have hurt themselves by encouraging their middle managers to stay extremely busy. In order to enable change, companies have to learn that keeping managers busy is a blunder. If you have busy managers working under you, they are an indictment of your vision and your capacity to transform that vision into reality. Cut them some slack.

-

Sufficient slack is not the only necessary ingredient for reinvention. Middle-level managers need to work together to conceive of and make any meaningful change happen. And middle managers almost never work together. In fact, managers at all levels tend to work in relative isolation.

-

I know from my early years of teaching development methods that when people learn something that really matters to them, they go through a moment of panic.

-

Most of us don’t learn well from abstraction. We learn from example. That’s part of the reason why we don’t learn well in isolation. The skills of management—like the skills of parenting—are best learned by example and with the help of able coaching and shared experience of peer learners.

-

When siblings are competitive, it’s often a result of being undernourished in some sense, feeling deprived of attention, affection, feedback, or approval. Maybe competition among peer managers and the danger in their white space are due to the same sort of undernourishment.

-

There is no such thing as “healthy” competition within a knowledge organization; all internal competition is destructive.

-

They reason that the obligations of “professionalism ” will oblige their subordinate managers to help each other out when it is in the common good. When that doesn’t happen, they grumble about “unprofessional” behavior. When peer managers play defense against each other (try to stop each other from scoring), they are engaging in anti-cooperation.

-

Training = practice by doing a new task much more slowly than an expert would do it Any so-called training experience that lacks the slow-down characteristic is an exercise in non-learning.

-

Instead of authority and consequence (the management staples of the factory floor), the best knowledge-work managers are known for their powers of persuasion, negotiation, markers to call in, and their large reserves of accumulated trust.

Risk management

-

Risk management is almost the opposite of Plan for Success. Risk management is—take a deep gulp of air here, this is going to be unsettling—a discipline of planning for failure.

-

The science of risk management guides you as to how much slack to provide.

- Risks are not inherently bad. (Risks are the entire reason there is money to be made in your business.)

- Risks don’t ever go entirely away. (You still have some loss when the bad thing happens.)

- Managing the risk costs you something (the work of laying off the extra policies and the penalty your partner companies may impose upon you before accepting some of your too-risky coverage.

- If the risk doesn’t materialize, risk management costs you something extra (the lost profit of all those property premiums in a year when there were no loss claims).

- The discipline is applied to the entire portfolio, not to any one of its constituent risks. (Having all your eggs in one basket—only one policy—gives you no way to assure that that policy won’t incur claims during the year.)

-

The control that risk management gives you is stochastic, not deterministic. Risk management (the simple definition) is the explicit declaration of uncertainty. It allows you to go forth into risky territory with some assurance of just how much risk you’re running. Explicit declaration of component uncertainties—the ones that lead to possible late delivery, for example—allow you to manage a sensible risk reserve across your whole set of risks to maximize the chances of overall success.

-

Most of the companies I know that have the 5 percent maximum uncertainty rule built into their corporate culture are far less successful at predicting than that. They regularly achieve results that deviate from prediction by 50 to 100 percent. With that kind of track record, insisting on a 5 percent maximum uncertainty window just makes liars out of everyone.

Can Do

-

Can Do is, unfortunately, antithetical to risk management. Risk management has to acknowledge directly the Can’t Do possibilities. There is no way to be a complete Can Do manager and also practice risk management.

-

There are two classes of risk that are handled somewhat differently: aggregate and component.

-

You can’t claim to be managing your risks unless you:

- List and count each risk.

- Have an ongoing process for discovering new risks.

- Quantify each one as to its potential impact and likelihood.

- Designate a transition indicator for each one that will tell you (early, I hope) that the risk is beginning to materialize.

- Set down in advance what your plan will be to cope with each risk should it begin to materialize.

-

The goal is to place in reserve enough time and money to give at least a fifty-fifty assurance that there will be enough to cover the costs of those risks that do materialize.

-

Setting aside a risk reserve with a 50 percent or better confidence level is called risk containment. When risks are paid for out of this reserve, they are said to be contained. It’s not a major intellectual effort to know how much time and money are needed to contain the most common risks of our work (half a dozen carefully performed project postmortems supply most of the data). The major effort is to keep the risk reserve from being eliminated by someone who wants desperately to hear lower numbers.

-

Risk mitigation is the set of actions you will take to reduce the impact of a risk should it materialize. There are two not-immediately-obvious aspects to risk mitigation: The plan has to precede materialization. Some of the mitigation activities must also precede materialization.

-

Proceeding at breakneck speed is, by definition, inconsistent with risk management. Of course you already knew that. But its corollary may have eluded you. The corollary is that managing your risks requires that you go at some slower speed. And the result is that you will finish later than you would have if you had sustained breakneck speed and been lucky enough not to break your neck.

-

The difference between the time it takes you to arrive at “all prudent speed ” and time it would take you at “breakneck speed” is your slack. Slack is what helps you arrive quickly but with an unbroken neck.

-

If you identify any project as risk-free, or even relatively risk-free, cancel it. You’re going to need the resources and calendar time to do something transformational.

Risk Management: The Hard Test

Pick a part of your company where the risks are greatest. It might be a scary project, one that the company’s future depends upon. It might be a new product development or a launch into untried markets. Now apply to it the following hard questions:

- Is there a published census of risks? Does the list contain the major causal risks, not just the few outcome risks that we all fear? Is the risk list visible to all who are working on the project Are there enough risks on the list to indicate careful risk analysis?

- Is there a mechanism in place to elicit discovery of new risks? Is it safe for all involved to signal a risk?

- Are any of the risks on the list potentially fatal? Risk management that concentrates only on risks that can be handled makes a mockery of the notion of risk management. It’s the fatal ones that need your most careful attention.

- Is each risk quantified as to probability and cost and schedule impact?

- Does each risk have a transition indicator allocated to it to spot materialization? Is each transition indicator being monitored?

- Is there a single person responsible for risk management? Where the attitude is that everybody is responsible for managing risks, nobody is responsible for it, since all those people have got Real Work on their plates.

- Are there tasks on the work breakdown structure that might not have to be done at all? The absence of such conditional tasks is a sure sign of no risk management at work.

- Does the overall effort have both a schedule and a goal, where the schedule and the goal are markedly different? If the schedule is the goal, there is no risk management at work. The earliest date by which the work could conceivably be done makes an excellent goal but an awful schedule.

- Is there a significant probability of finishing well before the estimated date? If there is not—if there is no reasonable probability of finishing 20 or 30 percent ahead of schedule—the schedule is a goal, not an estimate.

This is #65 in a series of book reviews published weekly on this site.