Omega: flexible, scalable schedulers for large compute clusters

What is this paper about?

This 2013 paper from Google introduces Omega, a new way to schedule computing jobs across massive clusters of machines. Think of a cluster scheduler as a traffic controller for thousands of computers - it decides which programs run on which machines and when. As Google's infrastructure grew, their existing scheduling system struggled to keep up with the scale and needed a rethink.

The core innovation: Instead of having one centralized scheduler or multiple schedulers fighting for resources, Omega uses multiple schedulers that all have access to the complete picture of available resources. They work independently and use a technique called "optimistic concurrency control" (explained below) to coordinate when they need to make changes.

Abstract (Original)

Increasing scale and the need for rapid response to changing requirements are hard to meet with current monolithic cluster scheduler architectures. This restricts the rate at which new features can be deployed, decreases efficiency and utilization, and will eventually limit cluster growth. We present a novel approach to address these needs using parallelism, shared state, and lock-free optimistic concurrency control. We compare this approach to existing cluster scheduler designs, evaluate how much interference between schedulers occurs and how much it matters in practice, present some techniques to alleviate it, and finally discuss a use case highlighting the advantages of our approach – all driven by real-life Google production workloads.

The Problem: How Should We Schedule Jobs?

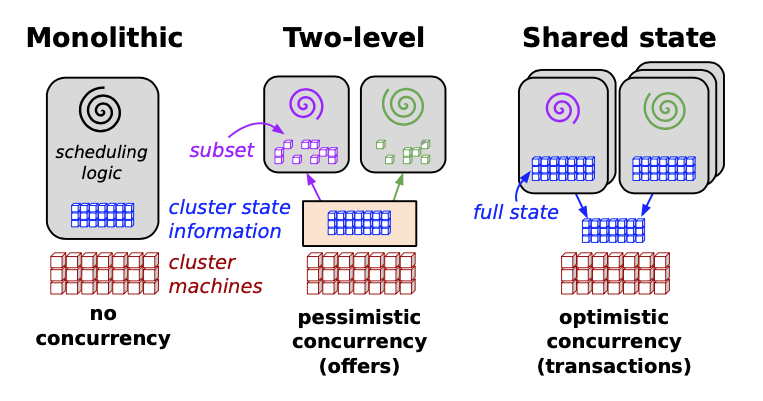

Before Omega, there were two main approaches to scheduling jobs in large compute clusters:

1. Monolithic schedulers - One big, centralized program handles all scheduling decisions for all jobs.

- Example: Google's Borg system (which was their production scheduler at the time)

- Problem: It's like having one person manage all the traffic lights in a huge city. Hard to add new features, difficult to scale, and becomes a bottleneck as the cluster grows.

2. Two-level schedulers - One central resource manager divides up resources among multiple independent scheduling systems.

- Examples: Apache Mesos, Hadoop-on-Demand

- Problem: To avoid conflicts, the resource manager uses conservative "locking" - it only shows each scheduler a portion of available resources. This means schedulers can't see the full picture, making it hard to place jobs with specific requirements (like a job that needs 1000 GPUs all connected on the same network).

Omega's solution: A new architecture built around "shared state" where multiple schedulers can all see the entire cluster and make decisions independently. When they try to claim resources, an "optimistic concurrency control" system handles any conflicts (more on this below).

What Does a Good Scheduler Need to Do?

A cluster scheduler at Google's scale has to juggle many competing demands:

- High resource utilization - Keep machines busy, don't waste expensive hardware

- Placement constraints - Respect requirements like "this job needs SSD storage" or "these tasks must be on the same rack"

- Fast decisions - Schedule jobs quickly so users aren't waiting

- Fairness and priority - Balance between different teams and different importance levels

- Reliability - The scheduler can never go down; it's critical infrastructure

Understanding the workload: Google's clusters handle two main types of jobs:

- Batch jobs - Short-lived data processing tasks (e.g., MapReduce jobs). These make up over 80% of the total number of jobs.

- Service jobs - Long-running services like web servers, which use 55-80% of total resources despite being fewer in number. These typically have fewer tasks but run for much longer.

How Omega Works: Shared-State Scheduling

The big idea: Give every scheduler full visibility into the entire cluster, let them work independently, and use "optimistic concurrency control" to handle conflicts when multiple schedulers want the same resources.

This solves the key problems of previous approaches:

- Unlike monolithic schedulers, multiple schedulers can work in parallel

- Unlike two-level schedulers, every scheduler sees the full picture of available resources

- The trade-off: Sometimes schedulers will conflict and need to retry their work

The architecture in detail:

1. Cell State - There's a master copy of all resource allocations in the cluster (which machines are running what jobs). This is the single source of truth.

2. Local Copies - Each scheduler gets its own frequently-updated copy of the cell state to work with. Think of this like getting a snapshot of the current state.

3. Making Changes - When a scheduler wants to place a job:

- It makes decisions based on its local copy

- It tries to update the master cell state in an "atomic commit" (all-or-nothing update)

- If another scheduler changed the same resources in the meantime, the conflict is detected

What is Optimistic Concurrency Control? Instead of locking resources upfront (pessimistic), Omega assumes conflicts will be rare and just checks at commit time. It's like assuming you'll get a seat at a restaurant and only dealing with the problem if it's full when you arrive, rather than calling ahead every time.

Handling Conflicts:

Incremental transactions (most common) - If there's a conflict, accept all changes except the conflicting ones. For example, if you're scheduling 100 tasks and only 5 conflict with another scheduler, place the other 95 and retry the 5. This prevents starvation where a scheduler never makes progress.

All-or-nothing transactions (gang scheduling) - Some jobs need all their tasks to run together (like a distributed training job that needs 100 GPUs simultaneously). In this case, either schedule all tasks or none. If resources aren't available, the scheduler retries later. This approach can also preempt (kick off) lower-priority tasks to make room when everything is ready.

Does It Actually Work? Performance Results

The paper compares Omega against both monolithic schedulers and Mesos (a two-level scheduler) using real Google workloads. Here are the key findings:

Conflicts are rare - Average job wait times for Omega are similar to optimized monolithic schedulers. This confirms that the optimistic concurrency approach works well in practice - schedulers don't step on each other's toes very often.

Omega schedules everything - Unlike Mesos, which struggled with some jobs because of limited resource visibility, Omega successfully scheduled all jobs in the test workload.

No head-of-line blocking - In monolithic schedulers, a difficult-to-place job can hold up the entire queue. Omega avoids this because batch jobs and service jobs have independent schedulers. If one scheduler is stuck on a hard problem, others keep making progress.

It scales - Tests showed Omega can handle many parallel schedulers and challenging workloads without performance degradation.

Easy to extend - The team built a prototype MapReduce scheduler as a proof of concept. Adding this specialized scheduler to Omega was straightforward, unlike their production monolithic system where adding new scheduling policies was complex and risky.

What Happened Next: The Legacy of Omega

Kubernetes builds on these ideas - If you've heard of Kubernetes (and you probably have - it's the dominant container orchestration platform today), you might be interested to know it was influenced by both Borg and Omega.

Kubernetes takes a middle-ground approach:

- It adopts Omega's modular, flexible architecture

- But it adds a centralized API server that all components must go through

- This API server enforces system-wide rules and policies while still allowing the flexibility Omega demonstrated

Read more in this related paper: Borg, Omega, and Kubernetes

Why Omega matters - Even though Omega itself was primarily a research system, it proved that:

- Optimistic concurrency control can work at massive scale

- Shared state doesn't have to be a bottleneck

- Flexible, multi-scheduler architectures are practical

- You can get both performance and extensibility

These insights influenced the design of modern cluster management systems that now run much of the world's cloud infrastructure.

Key Takeaways

If you remember nothing else from this paper, remember this:

- The core innovation - Multiple schedulers sharing complete cluster state, using optimistic concurrency control to coordinate

- The key insight - Conflicts in real workloads are rare enough that optimistic concurrency beats pessimistic locking

- The practical impact - Demonstrated that you can build flexible, scalable schedulers without sacrificing performance

- The influence - These ideas live on in Kubernetes and other modern cluster management systems

Further Reading

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #7 in this series.