Mesos: A Platform for Fine-Grained Resource Sharing in the Data Center

Abstract

We present Mesos, a platform for sharing commodity clusters between multiple diverse cluster computing frameworks, such as Hadoop and MPI. Sharing improves cluster utilization and avoids per-framework data replication. Mesos shares resources in a fine-grained manner, allowing frameworks to achieve data locality by taking turns reading data stored on each machine. To support the sophisticated schedulers of today’s frameworks, Mesos introduces a distributed two-level scheduling mechanism called resource offers. Mesos decides how many resources to offer each framework, while frameworks decide which resources to accept and which computations to run on them. Our results show that Mesos can achieve near-optimal data locality when sharing the cluster among diverse frameworks, can scale to 50,000 (emulated) nodes, and is resilient to failures.

Introduction

-

Organizations will want to run multiple frameworks in the same cluster, picking the best one for each application. Multiplexing a cluster between frameworks improves utilization and allows applications to share access to large datasets that may be too costly to replicate across clusters.

-

Two common solutions for sharing a cluster today are either to statically partition the cluster and run one framework per partition, or to allocate a set of VMs to each framework. Unfortunately, these solutions achieve neither high utilization nor efficient data sharing. There is no way to perform fine-grained sharing across frameworks, making it difficult to share clusters and data efficiently between them.

-

In this paper, the authors propose Mesos, a thin resource sharing layer that enables fine-grained sharing across diverse cluster computing frameworks, by giving frameworks a common interface for accessing cluster resources.

-

Why is designing a scalable and efficient system that supports a wide array of both current and future frameworks challenging?

- First, each framework will have different scheduling needs, based on its programming model, communication pattern, task dependencies, and data placement.

- Second, the scheduling system must scale to clusters of tens of thousands of nodes running hundreds of jobs with millions of tasks.

- Third, because all the applications in the cluster depend on Mesos, the system must be fault-tolerant and highly available.

-

Why did Mesos not implement a centralized scheduler that takes as input framework require- ments, resource availability, and organizational policies, and computes a global schedule for all tasks?

- First, this design would be complex.

- Second, as new frameworks and new scheduling policies for current frameworks are constantly being developed, it is not clear whether we are even at the point to have a full specification of framework requirements.

- Third, many existing frameworks implement their own sophisticated scheduling, and moving this functionality to a global scheduler would require expensive refactoring.

-

Instead, Mesos takes a different approach: delegating control over scheduling to the frameworks. This is accomplished through a new abstraction, called a resource offer, which encapsulates a bundle of resources that a framework can allocate on a cluster node to run tasks.

- Mesos decides how many resources to offer each framework, while frameworks decide which resources to accept and which tasks to run on them.

- Resource offers are simple and efficient to implement, allowing Mesos to be highly scalable and robust to failures.

-

Mesos also provides other benefits to practitioners:

- Run multiple instances of that framework in the same cluster, or multiple versions of the framework.

- Provide a compelling way to isolate production and experimental Hadoop workloads and to roll out new versions of Hadoop.

- Immediately experiment with new frameworks.

-

Mesos is implemented in 10,000 lines of C++ and scales to 50,000 (emulated) nodes and uses ZooKeeper for fault tolerance.

-

The authors have also built a new framework on top of Mesos called Spark, optimized for iterative jobs where a dataset is reused in many parallel operations, and shown that Spark can outperform Hadoop by 10x in iterative machine learning workloads.

Target Environment

-

Most jobs are short (the median job being 84s long), and the jobs are composed of fine-grained map and reduce tasks (the median task being 23s). For example, 1-2 minute ad-hoc queries submitted interactively through an SQL interface called Hive.

-

Facebook uses a fair scheduler for Hadoop that takes advantage of the fine-grained nature of the workload to allocate resources at the level of tasks and to optimize data locality. Unfortunately, this means that the cluster can only run Hadoop jobs.

Architecture

-

Pushing control of task scheduling and execution to the frameworks:

- First, it allows frameworks to implement diverse approaches to various problems in the cluster.

- Second, it keeps Mesos simple and minimizes the rate of change required of the system, which makes it easier to keep Mesos scalable and robust.

-

Authors expect higher-level libraries implementing common functionality (such as fault tolerance) to be built on top of Mesos.

-

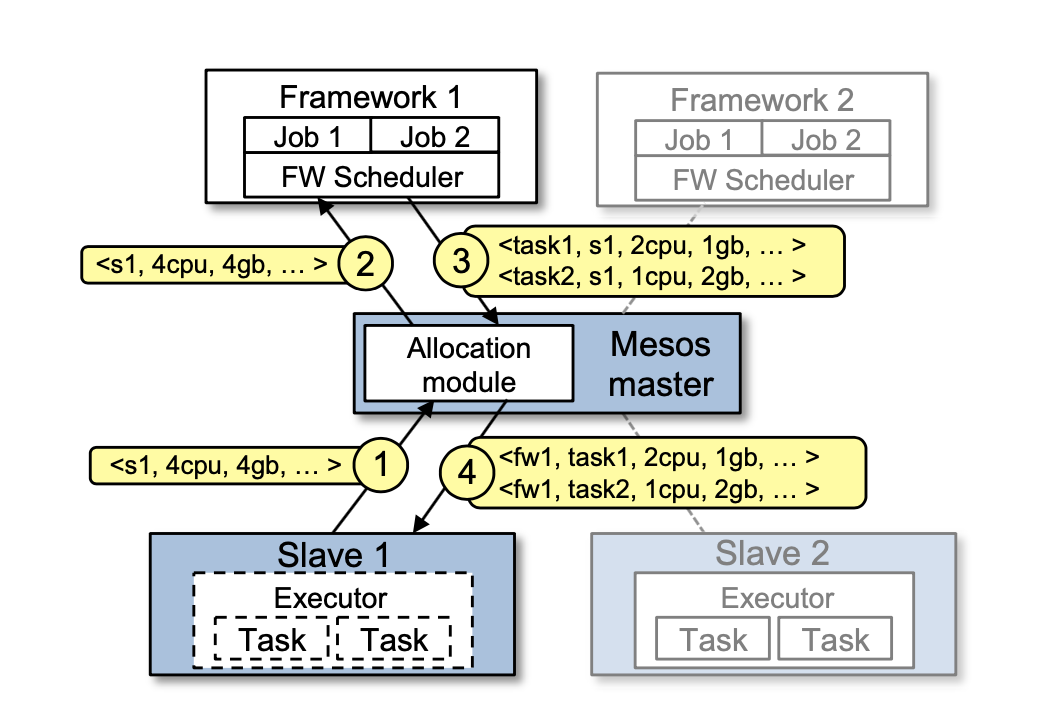

Mesos consists of a master process that manages slave daemons running on each cluster node, and frameworks that run tasks on these slaves.

-

Each resource offer is a list of free resources on multiple slaves.

-

Mesos lets organizations define their own policies via a pluggable allocation module.

-

Each framework running on Mesos consists of two components: a scheduler that registers with the master to be offered resources, and an executor process that is launched on slave nodes to run the framework’s tasks.

-

While the master determines how many resources to offer to each framework, the frameworks’ schedulers select which of the offered resources to use.

-

Mesos does not require frameworks to specify their resource requirements or constraints. Instead, Mesos gives frameworks the ability to reject offers. A framework can reject resources that do not satisfy its constraints in order to wait for ones that do.

-

A framework may have to wait a long time before it receives an offer satisfying its constraints, and Mesos may have to send an offer to many frameworks before one of them accepts it. To avoid this, Mesos also allows frameworks to set filters, which are Boolean predicates specifying that a framework will always reject certain resources.

- Filters represent just a performance optimization.

- When the workload consists of fine-grained tasks (e.g., in MapReduce and Dryad workloads), the resource offer model performs surprisingly well even in the absence of filters: A simple policy called delay scheduling, in which frameworks wait for a limited time to acquire nodes storing their data, yields nearly optimal data locality with a wait time of 1-5s.

-

Mesos takes advantage of the fact that most tasks are short, and only reallocates resources when tasks finish. For example, if a framework’s share is 10% of the cluster, it needs to wait approximately 10% of the mean task length to receive its share. However, if a cluster becomes filled by long tasks, e.g., due to a buggy job or a greedy framework, the allocation module can also revoke (kill) tasks. Before killing a task, Mesos gives its framework a grace period to clean it up.

-

It is left up to the allocation module to select the policy for revoking tasks:

- It is harmful for frameworks with interdependent tasks (e.g., MPI).

- Letting allocation modules expose a guaranteed allocation to each framework — a quantity of resources that the framework may hold without losing tasks.

- If a framework is below its guaranteed allocation, none of its tasks should be killed, and if it is above, any of its tasks may be killed.

- Second, to decide when to trigger revocation, Mesos must know which of the connected frameworks would use more resources if they were offered them. Frameworks indicate their interest in offers through an API call.

-

Isolation: by leveraging existing OS isolation mechanisms. Since these mechanisms are platform-dependent, they support multiple isolation mechanisms through pluggable isolation modules.

-

Making Resource Offers Scalable and Robust:

- Filters: currently support two types of filters: “only offer nodes from list L” and “only offer nodes with at least R resources free”. Filters are Boolean predicates that specify whether a framework will reject one bundle of resources on one node, so they can be evaluated quickly on the master.

- Second, Mesos counts resources offered to a framework towards its allocation of the cluster.

- Third, if a framework has not responded to an offer for a sufficiently long time, Mesos rescinds the offer and re-offers the resources to other frameworks.

-

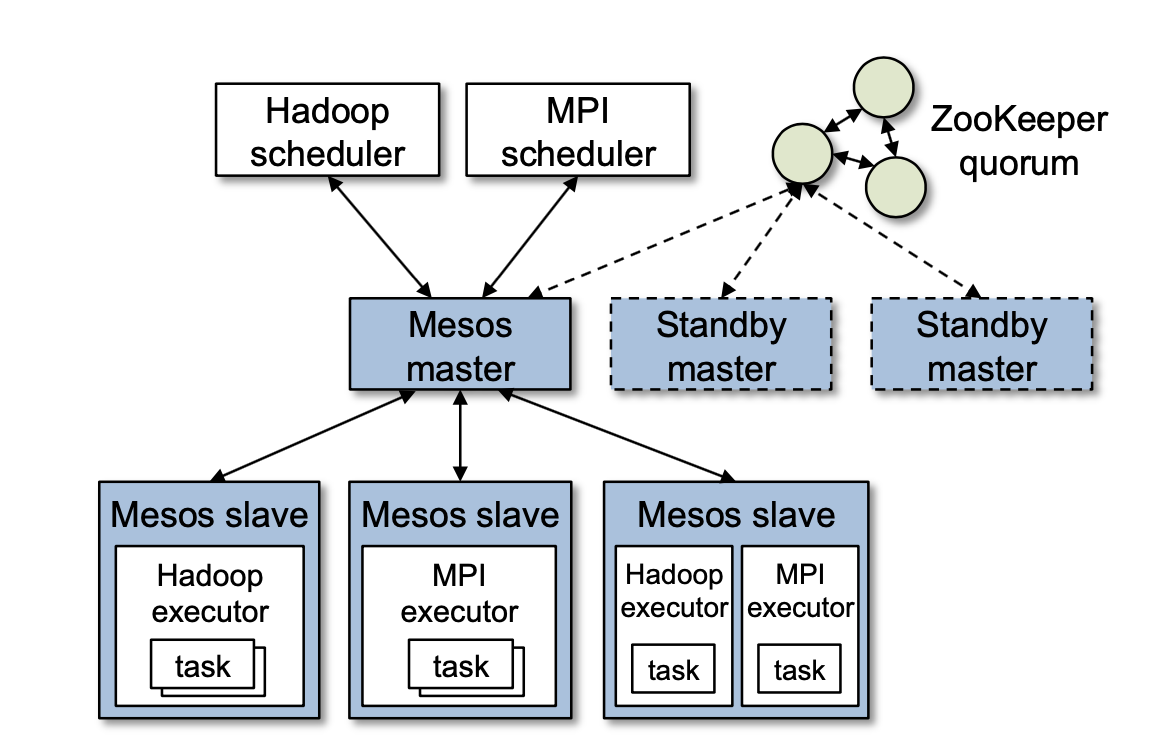

Fault Tolerance:

- The master is designed to be soft state, so that a new master can completely reconstruct its internal state from information held by the slaves and the framework schedulers. The master’s only state is the list of active slaves, active frameworks, and running tasks.

- They run multiple masters in a hot-standby configuration using ZooKeeper for leader election.

- Mesos reports node failures and executor crashes to frameworks’ schedulers. Frameworks can then react to these failures using the policies of their choice.

- Mesos allows a framework to register multiple schedulers such that when one fails, another one is notified by the Mesos master to take over.

Mesos Behavior

Mesos performs very well when frameworks can scale up and down elastically, tasks durations are homogeneous, and frameworks prefer all nodes equally. When different frameworks prefer different nodes, we show that Mesos can emulate a centralized scheduler that performs fair sharing across frameworks.

-

An elastic framework, such as Hadoop and Dryad, can scale its resources up and down, i.e., it can start using nodes as soon as it acquires them and release them as soon its task finish. In contrast, a rigid framework, such as MPI, can start running its jobs only after it has acquired a fixed quantity of resources, and cannot scale up dynamically to take advantage of new resources or scale down without a large impact on performance. Elastic frameworks with constant task durations perform the best, while rigid frameworks with exponential task duration perform the worst.

-

They also differentiate between two types of resources: mandatory and preferred.

-

For simplicity, we also assume that all tasks have the same resource demands and run on identical slices of machines called slots, and that each framework runs a single job.

-

How well Mesos will work compared to a central scheduler that has full information about framework preferences? There are two scenarios to judge:

- (a) there exists a system configuration in which each framework gets all its preferred slots and achieves its full allocation. It is easy to see that, irrespective of the initial configuration, the system will converge to the state where each framework allocates its preferred slots after at most one mean task duration interval.

- (b) there is no such configuration, i.e., the demand for some preferred slots exceeds the supply. Simply perform lottery scheduling, offering slots to frameworks with probabilities proportional to their intended allocations is an easy way to achieve the weighted allocation of the preferred slots described above.

-

For task durations, we consider both homogeneous and heterogeneous distributions.

- In the worst case, all nodes required by a short job might be filled with long tasks, so the job may need to wait a long time (relative to its execution time) to acquire resources.

- Random task assignment can work well if the fraction φ of long tasks is not very close to 1 and if each node supports multiple slots.

- Thus, a framework with short tasks can still acquire many preferred slots in a short period of time

- To further alleviate the impact of long tasks, Mesos can be extended slightly to allow allocation policies to reserve some resources on each node for short tasks. In particular, we can associate a maximum task duration with some of the resources on each node, after which tasks running on those resources are killed.

- This scheme is similar to the common policy of having a separate queue for short jobs in HPC clusters.

-

Framework incentives: As with any decentralized system, it is important to understand the incentives of entities in the system. Mesos incentivizes frameworks as follows:

- Short tasks

- Scale elastically

- Do not accept unknown resources

-

Limitations of Distributed Scheduling

- Fragmentation: clusters running “larger” nodes (e.g., multicore nodes) and “smaller” tasks within those nodes will achieve high utilization even with distributed scheduling. To accommodate frameworks with large per-task resource requirements, allocation modules can support a minimum offer size on each slave, and abstain from offering resources on the slave until this amount is free.

- Interdependent framework constraints: It is possible to construct scenarios where, because of esoteric interdependencies between frameworks (e.g., certain tasks from two frameworks cannot be co-located), only a single global allocation of the cluster performs well.

- Framework complexity: Using resource offers may make framework scheduling more complex. This difficulty is not onerous due to two reasons. First, whether using Mesos or a centralized scheduler, frameworks need to know their preferences. Second, many scheduling policies for existing frameworks are online algorithms, because frameworks cannot predict task times and must be able to handle failures and stragglers. These policies are easy to implement over resource offers.

Implementation

-

Used a C++ library called

libprocessthat provides an actor-based programming model using efficient asynchronous I/O mechanisms (epoll, kqueue, etc). They also use ZooKeeper to perform leader election. -

They use delay scheduling to achieve data locality by waiting for slots on the nodes that contain task input data.

-

Hadoop port is 1500 lines of code. Because jobs that run on Torque (e.g. MPI) may not be fault tolerant, Torque avoids having its tasks revoked by not accepting resources beyond its guaranteed allocation.

Spark Framework

-

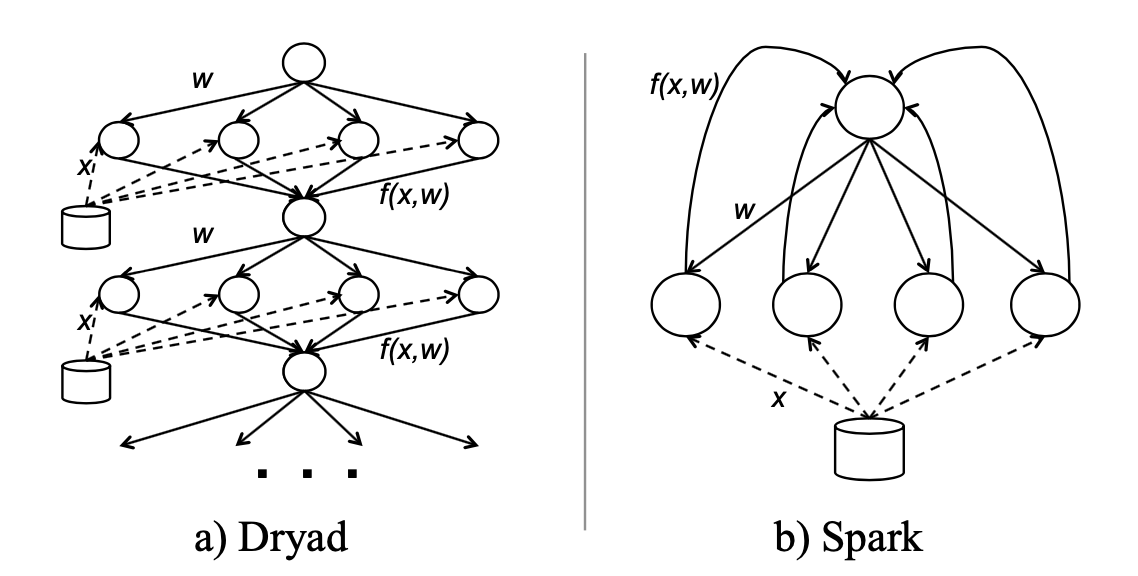

To test the hypothesis that simple specialized frameworks provide value, we identified one class of jobs that were found to perform poorly on Hadoop by machine learning researchers at our lab: iterative jobs, where a dataset is reused across a number of iterations. We built a specialized framework called Spark optimized for these workloads. An example of such workload is logistic regression.

-

An implementation of logistic regression in Hadoop must run each iteration as a separate MapReduce job, because each iteration depends on the

wcomputed at the previous one. This imposes overhead because every iteration must re-read the input file into memory. In Dryad, the whole job can be expressed as a data flow DAG as shown in the figure below, but the data must still must be reloaded from disk at each iteration.

-

Spark uses the long-lived nature of Mesos executors to cache a slice of the dataset in memory at each executor, and then run multiple iterations on this cached data.

-

This caching is achieved in a fault-tolerant manner: if a node is lost, Spark remembers how to recompute its slice of the data. By building Spark on top of Mesos, we were able to keep its implementation small (about 1300 lines of code), yet still capable of outperforming Hadoop by 10× for iterative jobs.

-

Using Mesos’s API saved us the time to write a master daemon, slave daemon, and communication protocols between them for Spark. The main pieces we had to write were a framework scheduler (which uses delay scheduling for locality) and user APIs.

Evaluation

They compared a scenario where the workloads ran as four frameworks on a 96-node Mesos cluster using fair sharing to a scenario where they were each given a static partition of the cluster (24 nodes), and measured job response times and resource utilization in both cases. We used EC2 nodes with 4 CPU cores and 15 GB of RAM.

-

Mesos achieves higher utilization than static partitioning, and that jobs finish at least as fast in the shared cluster as they do in their static partition, and possibly faster due to gaps in the demand of other frameworks. The results show both effects.

-

Higher allocation of nodes also translates into increased CPU and memory utilization (by 10% for CPU and 17% for memory)

-

We see that the fine-grained frameworks (Hadoop and Spark) take advantage of Mesos to scale up beyond 1/4 of the cluster when global demand allows this, and consequently finish bursts of submitted jobs faster in Mesos.

-

The framework that gains the most is the large-job Hadoop mix, which almost always has tasks to run and fills in the gaps in demand of the other frameworks; this framework performs 2x better on Mesos.

-

In contrast, when running alone, Hadoop can assign resources to the new job as soon as any of its tasks finishes. This problem with hierarchical fair sharing is also seen in networks, and could be mitigated by running the small jobs on a separate framework or using a different allocation policy.

-

Overhead: The MPI job took on average 50.9s without Mesos and 51.8s with Mesos, while the Hadoop job took 160s without Mesos and 166s with Mesos. In both cases, the overhead of using Mesos was less than 4%.

-

Data Locality through Delay Scheduling: tatic partitioning yields very low data locality (18%). Mesos improves data locality, even without delay scheduling, because each Hadoop instance has tasks on more nodes of the cluster (there are 4 tasks per node), and can therefore access more blocks locally. Adding a 1-second delay brings locality above 90%, and a 5-second delay achieves 95% locality, which is competitive with running one Hadoop instance alone on the whole cluster. Jobs run 1.7x faster in the 5s delay scenario than with static partitioning.

-

Spark Framework: With Hadoop, each iteration takes 127s on average, because it runs as a separate MapReduce job. In contrast, with Spark, the first iteration takes 174s, but subsequent iterations only take about 6 seconds, leading to a speedup of up to 10x for 30 iterations.

-

Scalability: Once the cluster reached steady-state, they launched a test framework that runs a single 10 second task and measured how long this framework took to finish They observe that the overhead remains small (less than one second) even at 50,000 nodes

-

Failure recovery: Mean time to recovery (MTTR) was between 4 and 8 seconds, with 95% confidence intervals of up to 3s on either side.

Related Work

-

HPC and Grid Schedulers have specialized hardware as their target environment. HPC schedulers use centralized scheduling, and require users to declare the required resources at job submission time. Mesos supports fine-grained sharing at the level of tasks and allows frameworks to control their placement.

-

Public and Private Clouds: First, their relatively coarse grained VM allocation model leads to less efficient resource utilization and data sharing than in Mesos. In contrast, Mesos allows frameworks to be highly selective about task placement.

Conclusion

Mesos describes a distributed scheduling mechanism called resource offers that delegates scheduling decisions to the frameworks.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #16 in this series.