MapReduce: Simplified Data Processing on Large Clusters

Abstract

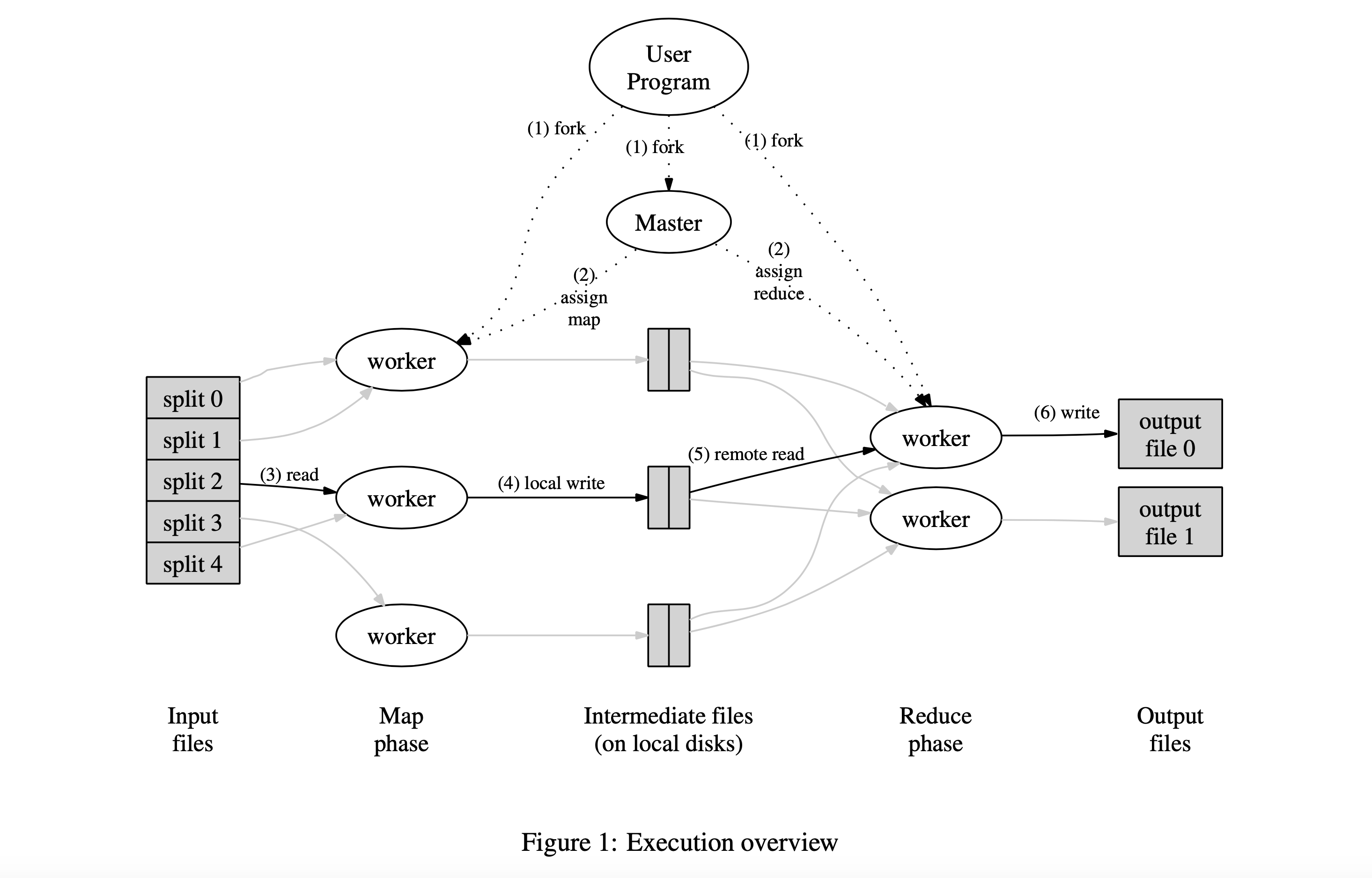

MapReduce is a programming model and an associated implementation for processing and generating large data sets. Users specify a map function that processes a key/value pair to generate a set of intermediate key/value pairs, and a reduce function that merges all intermediate values associated with the same intermediate key. Many real world tasks are expressible in this model, as shown in the paper. Programs written in this functional style are automatically parallelized and executed on a large cluster of commodity machines. The run-time system takes care of the details of partitioning the input data, scheduling the program’s execution across a set of machines, handling machine failures, and managing the required inter-machine communication. This allows programmers without any experience with parallel and distributed systems to easily utilize the resources of a large distributed system. Our implementation of MapReduce runs on a large cluster of commodity machines and is highly scalable: a typical MapReduce computation processes many terabytes of data on thousands of machines. Programmers find the system easy to use: hundreds of MapReduce programs have been implemented and upwards of one thousand MapReduce jobs are executed on Google’s clusters every day.

Programming Model

- The computation takes a set of input key/value pairs, and produces a set of output key/value pairs.

- The user of the MapReduce library expresses the computation as two functions:

MapandReduce. Map, written by the user, takes an input pair and produces a set ofintermediatekey/value pairs. The MapReduce library groups together allintermediatevalues associated with the sameintermediatekeyIand passes them to theReducefunction.- The

Reducefunction, also written by the user, accepts anintermediatekeyIand a set of values for that key. It merges together these values to form a possibly smaller set of values. - Typically just zero or one output value is produced per

Reduceinvocation. - The intermediate values are supplied to the user’s

Reducefunction via an iterator. This allows us to handle lists of values that are too large to fit in memory. - In addition, the user writes code to fill in a mapreduce specification object with the names of the input and output files, and optional tuning parameters.

- Types:

map (k1,v1) → list(k2,v2) reduce (k2,list(v2)) → list(v2) - Some examples: Distributed Grep, Count of URL Access Frequency, Reverse Web-Link Graph, Term-Vector per Host, Inverted Index, Distributed Sort.

Design Choices

1. Fault Tolerance

- Worker Failure: Completed map tasks are re-executed on a failure because their output is stored on the local disk(s) of the failed machine and is therefore inaccessible. Completed reduce tasks do not need to be re-executed since their output is stored in a global file system.

- Master Failure: It is easy to make the master write periodic checkpoints of the master data structures described above. If the master task dies, a new copy can be started from the last checkpointed state. However, given that there is only a single master, its failure is unlikely; therefore the current implementation aborts the MapReduce computation if the master fails.

- Non-deterministic operators: In the presence of non-deterministic operators, the output of a particular reduce task R1 is equivalent to the output for R1 produced by a sequential execution of the non-deterministic program. However, the output for a different reduce task R2 may correspond to the output for R2 produced by a different sequential execution of the non-deterministic program.

2. Locality

The MapReduce master takes the location information of the input files into account and attempts to schedule a map task on a machine that contains a replica of the corresponding input data. Failing that, it attempts to schedule a map task near a replica of that task’s input data.

3. Task Granularity

- Ideally,

MandR, the number ofMapandReducetasks, respectively, should be much larger than the number of worker machines. Having each worker perform many different tasks improves dynamic load balancing, and also speeds up recovery when a worker fails: the many map tasks it has completed can be spread out across all the other worker machines. - There are practical bounds on how large

MandRcan be in the implementation, since the master must makeO(M + R)scheduling decisions and keepsO(M * R)state in memory. - Furthermore,

Ris often constrained by users because the output of each reduce task ends up in a separate output file. - In practice, tend to choose

Mso that each individual task is roughly 16 MB to 64 MB of input data (so that the locality optimization described above is most effective), and makeRa small multiple of the number of worker machines expected to use. - Often perform MapReduce computations with

M= 200,000 andR= 5,000, using 2,000 worker machines.

4. Backup Tasks

- “Straggler”: a machine that takes an unusually long time to complete one of the last few map or reduce tasks in the computation.

- When a MapReduce operation is close to completion, the master schedules backup executions of the remaining in-progress tasks. The task is marked as completed whenever either the primary or the backup execution completes.

- Tuned this mechanism so that it typically increases the computational resources used by the operation by no more than a few percent. They found that this significantly reduces the time to complete large MapReduce operations.

5. Combiner Function

Allow the user to specify an optional Combiner function that does partial merging of this data before it is sent over the network. Typically the same code is used to implement both the combiner and the reduce functions. The only difference between a reduce function and a combiner function is how the MapReduce library handles the output of the function.

6. Input types

Users can add support for a new input type by providing an implementation of a simple reader interface, though most users just use one of a small number of predefined input types. A reader does not necessarily need to provide data read from a file. For example, it is easy to define a reader that reads records from a database, or from data structures mapped in memory.

7. Side Effects

In some cases, users of MapReduce have found it convenient to produce auxiliary files as additional outputs from their map and/or reduce operators. Application writer should make such side-effects atomic and idempotent. Typically the application writes to a temporary file and atomically renames this file once it has been fully generated. Tasks that produce multiple output files with cross-file consistency requirements should be deterministic. No support for atomic two-phase commits of multiple output files produced by a single task.

8. Skipping Bad Records

MapReduce provide an optional mode of execution where the MapReduce library detects which records cause deterministic crashes and skips these records in order to make forward progress. When the master has seen more than one failure on a particular record, it indicates that the record should be skipped when it issues the next re-execution of the corresponding Map or Reduce task.

9. Local Execution

Controls are provided to the user so that the computation can be limited to particular map tasks. Users invoke their program with a special flag and can then easily use any debugging or testing tools they find useful (e.g. gdb).

10. Status Information

The master runs an internal HTTP server and exports a set of status pages for human consumption.

11. Counters

The MapReduce library provides a counter facility to count occurrences of various events. For example, user code may want to count total number of words processed or the number of German documents indexed, etc. The counter values from individual worker machines are periodically propagated to the master (piggybacked on the ping response). Some counter values are automatically maintained by the MapReduce library, such as the number of input key/value pairs processed and the number of output key/value pairs produced.

Usage

MapReduce has been used across a wide range of domains within Google, including:

- large-scale machine learning problems,

- clustering problems for the Google News and Froogle products,

- extraction of data used to produce reports of popular queries (e.g. Google Zeitgeist),

- extraction of properties of web pages for new experiments and products (e.g. extraction of geographical locations from a large corpus of web pages for localized search), and

- large-scale graph computations.

MapReduce has been so successful because it makes it possible to write a simple program and run it efficiently on a thousand machines in the course of half an hour, greatly speeding up the development and prototyping cycle.

Conclusion

- MapReduce is easy to use, even for programmers without experience with parallel and distributed systems, since it hides the details of parallelization, fault-tolerance, locality optimization, and load balancing.

- a large variety of problems are easily expressible as MapReduce computations.

- they have developed an implementation of MapReduce that scales to large clusters of machines comprising thousands of machines.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #3 in this series.