Breaking neural networks with adversarial attacks

As many of you may know, Deep Neural Networks are highly expressive machine learning networks that have been around for many decades. In 2012, with gains in computing power and improved tooling, a family of these machine learning models called ConvNets started achieving state of the art performance on visual recognition tasks. Up to this point, machine learning algorithms simply didn’t work well enough for anyone to be surprised when it failed to do the right thing.

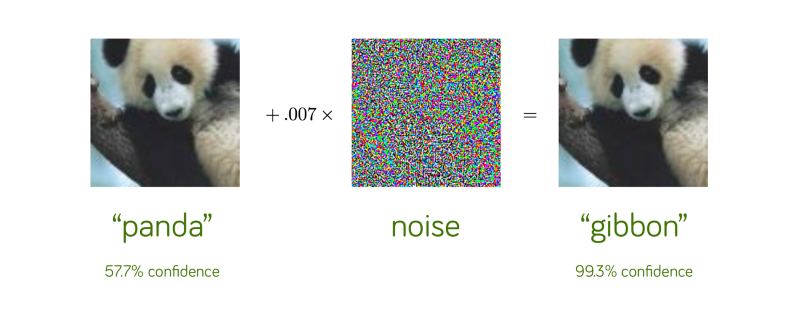

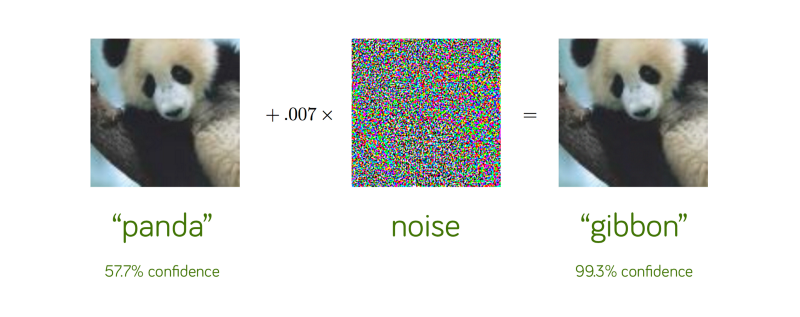

In 2014, a group of researchers at Google and NYU found that it was far too easy to fool ConvNets with an imperceivable, but carefully constructed nudge in the input. Let’s look at an example. We start with an image of a panda, which our neural network correctly recognizes as a “panda” with 57.7% confidence. Add a little bit of carefully constructed noise and the same neural network now thinks this is an image of a gibbon with 99.3% confidence! This is, clearly, an optical illusion — but for the neural network. You and I can clearly tell that both the images look like pandas — in fact, we can’t even tell that some noise has been added to the original image to construct the adversarial example on the right!

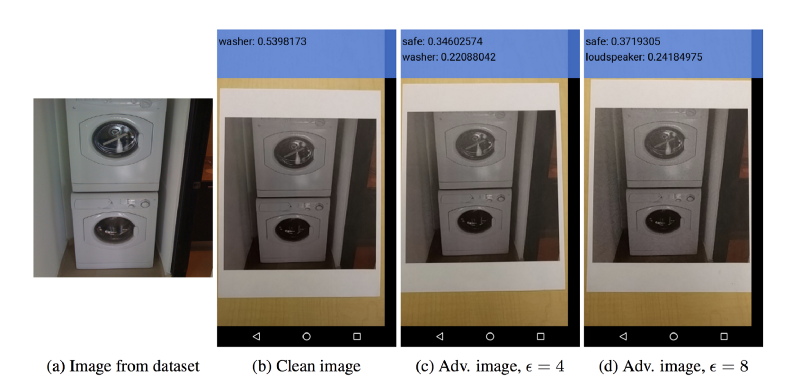

In 2017, another group demonstrated that it’s possible for these adversarial examples to generalize to the real world by showing that when printed out, an adversarially constructed image will continue to fool neural networks under different lighting and orientations:

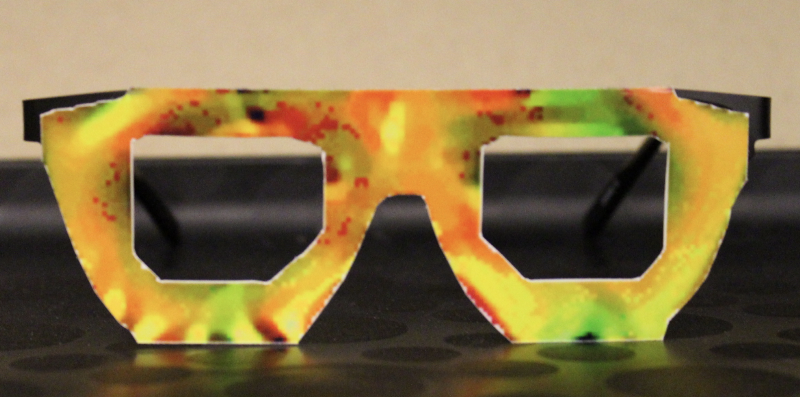

Another interesting work, titled “Accessorize to a Crime: Real and Stealthy Attacks on State-of-the-Art Face Recognition” showed that one can fool facial recognition software by constructing adversarial glasses by dodging face detection altogether. These glasses could let you impersonate someone else as well:

Shortly after, another research group demonstrated various methods for constructing stop signs that can fool models by placing various stickers on a stop sign. The perturbations were designed to mimic graffiti, and thus “hide in the human psyche.”

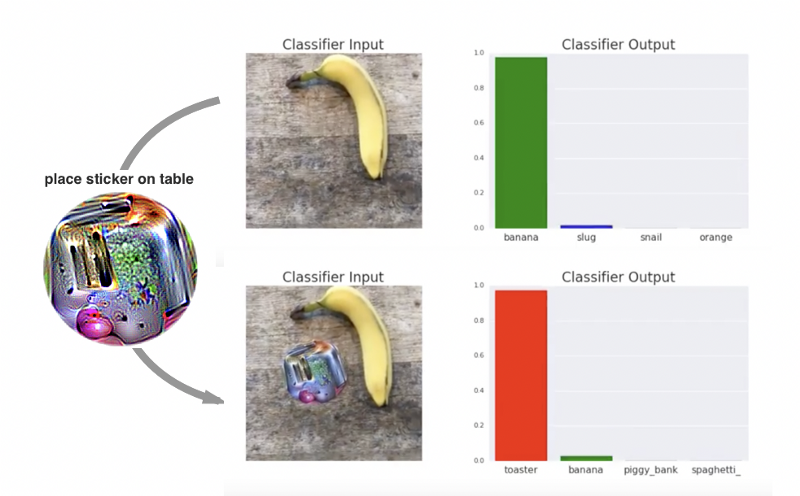

“Adversarial Patch”, a paper published at NIPS 2017 demonstrated how to generate a patch that can be placed anywhere within the field of view of the classifier and cause the classifier to output a targeted class. In the video below, a banana is correctly classified as a banana. Placing a sticker with a toaster printed on it is not enough to fool the network and it still continues to classify it as a banana. However, with a carefully constructed “adversarial patch”, it’s easy to trick the network into thinking that it’s a toaster:

To quote the authors, “this attack was significant because the attacker does not need to know what image they are attacking when constructing the attack. After generating an adversarial patch, the patch could be widely distributed across the Internet for other attackers to print out and use.”

What these examples show us is that our neural networks are still quite fragile when explicitly attacked by an adversary in this way. Let’s dive deeper!

What’s so remarkable about these attacks?

First, as we saw above, it’s easy to attain high confidence in the incorrect classification of an adversarial example — recall that in the first “panda” example we looked at, the network is less sure of an actual image looking like a panda (57.7%) than our adversarial example on the right looking like a gibbon (99.3%). Another intriguing point is how imperceptibly little noise we needed to add to fool the system — after all, clearly, the added noise is not enough to fool us, the humans.

Second, the adversarial examples don’t depend much on the specific deep neural network used for the task — an adversarial example trained for one network seems to confuse another one as well. In other words, multiple classifiers assign the same (wrong) class to an adversarial example. This “transferability” enables attackers to fool systems in what are known as “black-box attacks” where they don’t have access to the model’s architecture, parameters or even the training data used to train the network.

Do we have good defenses?

Not really. Let’s quickly look at two categories of defenses that have been proposed so far:

Adversarial training

One of the easiest and most brute-force way to defend against these attacks is to pretend to be the attacker, generate a number of adversarial examples against your own network, and then explicitly train the model to not be fooled by them. This improves the generalization of the model but hasn’t been able to provide a meaningful level of robustness — in fact, it just ends up being a game of whack-a-mole where attackers and defenders are just trying to one-up each other.

Defensive distillation

In defensive distillation, we train a secondary model whose surface is smoothed in the directions an attacker will typically try to exploit, making it difficult for them to discover adversarial input tweaks that lead to incorrect categorization. The reason it works is that unlike the first model, the second model is trained on the primary model’s “soft” probability outputs, rather than the “hard” (0/1) true labels from the real training data. This technique was shown to have some success defending initial variants of adversarial attacks but has been beaten by more recent ones, like the Carlini-Wagner attack, which is the current benchmark for evaluating the robustness of a neural network against adversarial attacks.

Why is defending neural networks so hard?

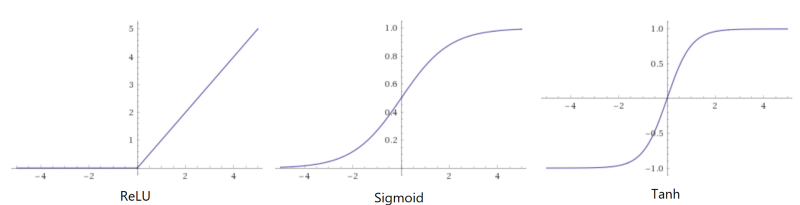

Let’s try to develop an intuition behind what’s going on here. Most of the time, machine learning models work very well but only work on a very small amount of all the many possible inputs they might encounter. In a high-dimensional space, a very small perturbation in each individual input pixel can be enough to cause a dramatic change in the dot products down the neural network. So, it’s very easy to nudge the input image to a point in high-dimensional space that our networks have never seen before. This is a key point to keep in mind: the high dimensional spaces are so sparse that most of our training data is concentrated in a very small region known as the manifold. Although our neural networks are nonlinear by definition, the most common activation function we use to train them, the Rectifier Linear Unit, or ReLu, is linear for inputs greater than 0.

ReLu became the preferred activations function due to its ease of trainability. Compared to sigmoid or tanh activation functions that simply saturate to a capped value at high activations and thus have gradients getting “stuck” very close to 0, the ReLu has a non-zero gradient everywhere to the right of 0, making it much more stable and faster to train. But, that also makes it possible to push the ReLu activation function to arbitrarily high values.

Looking at this trade-off between trainability and robustness to adversarial attacks, we can conclude that the neural network models we have been using are intrinsically flawed. Ease of optimization has come at the cost of models that are easily misled.

What’s next?

The real problem here is that our machine learning models exhibit unpredictable and overly confident behavior outside of the training distribution. Adversarial examples are just a subset of this broader problem. We would like our models to be able to exhibit appropriately low confidence when they’re operating in regions they have not seen before. We want them to “fail gracefully” when used in production.

According to Ian Goodfellow, one of the pioneers of this field, “many of the most important problems still remain open, both in terms of theory and in terms of applications. We do not yet know whether defending against adversarial examples is a theoretically hopeless endeavor or if an optimal strategy would give the defender an upper ground. On the applied side, no one has yet designed a truly powerful defense algorithm that can resist a wide variety of adversarial example attack algorithms.”

If nothing else, the topic of adversarial examples gives us an insight into what most researchers have been saying for a while — despite the breakthroughs, we are still in the infancy of machine learning and still have a long way to go here. Machine Learning is just another tool, susceptible to adversarial attacks which can have huge implications in a world where we trust them with human lives via self-driving cars and other automation.

References

Here are the links to the papers referenced above. I also highly recommend checking out Ian Goodfellow’s blog on the topic.

- Explaining and Harnessing Adversarial Examples, Goodfellow et al, ICLR 2015.

- Adversarial Examples in the Physical World. Kurakin et al, ICLR 2017.

- Accessorize to a Crime: Real and Stealthy Attacks on State-of-the-Art Face Recognition. Sharif et al.

- Robust Physical-World Attacks on Deep Learning Visual Classification. Eykholt et al.

- Adversarial Patch. Brown et al.