Large-scale cluster management at Google with Borg

Abstract

Google’s Borg system is a cluster manager that runs hundreds of thousands of jobs, from many thousands of different applications, across a number of clusters each with up to tens of thousands of machines. It achieves high utilization by combining admission control, efficient task-packing, over-commitment, and machine sharing with process-level performance isolation. It supports high-availability applications with runtime features that minimize fault-recovery time, and scheduling policies that reduce the probability of correlated failures. Borg simplifies life for its users by offering a declarative job specification language, name service integration, real-time job monitoring, and tools to analyze and simulate system behavior. We present a summary of the Borg system architecture and features, important design decisions, a quantitative analysis of some of its policy decisions, and a qualitative examination of lessons learned from a decade of operational experience with it.

Introduction

The cluster management system internally called Borg at Google admits, schedules, starts, restarts, and monitors the full range of applications that Google runs. This paper explains how. Borg provides three main benefits:

- Hides the details of resource management and failure handling so its users can focus on application development instead.

- Operates with very high reliability and availability, and supports applications that do the same.

- Lets operators run workloads across tens of thousands of machines effectively.

Distributed storage systems such as GFS and its successor CFS, Bigtable, and Megastore all run on Borg.

High-level architecture

Users submit their work to Borg in the form of jobs, each of which consists of one or more tasks that all run the same program (binary). Each job runs in one Borg cell, a set of machines that are managed as a unit.

-

Borg cells run a heterogenous workload with two main parts. The first is long-running services that should “never” go down. The second is batch jobs that take from a few seconds to a few days to complete. Most long-running server jobs are prod; most batch jobs are non-prod.

-

A cluster lives inside a single datacenter building, and a collection of buildings makes up a site. A cluster usually hosts one large cell and may have a few smaller-scale test or special-purpose cells. We assiduously avoid any single point of failure. Median cell size is about 10k machines after excluding test cells.

-

Borg programs are statically linked to reduce dependencies on their runtime environment, and structured as packages of binaries and data files, whose installation is orchestrated by Borg.

-

Most job descriptions are written in the declarative configuration language BCL. Borg job configurations have similarities to Aurora configuration files.

-

Alloc: A Borg alloc (short for allocation) is a reserved set of resources on a machine in which one or more tasks can be run; the resources remain assigned whether or not they are used. An alloc set is like a job. We generally use “task” to refer to an alloc or a top-level task (one outside an alloc) and “job” to refer to a job or alloc set.

-

Priority: Priority, a small positive integer. Borg defines non-overlapping priority bands, in decreasing order: monitoring, production, batch, and best effort (also known as testing or free). Prod jobs are the ones in the monitoring and production bands.

-

To avoid preemption cascades, they disallow tasks in the production priority band to preempt one another.

-

MapReduce master tasks run at a slightly higher priority than the workers they control, to improve their reliability.

-

-

Quota is used to decide which jobs to admit for scheduling. Quota is expressed as a vector of resource quantities (CPU, RAM, disk, etc.) at a given priority, for a period of time (typically months).

-

Quota-checking is part of admission control, not scheduling.

-

Even though they encourage users to purchase no more quota than they need, many users overbuy because it insulates them against future shortages when their application’s user base grows. We respond to this by over-selling quota at lower-priority levels: every user has infinite quota at priority zero, although this is frequently hard to exercise because resources are oversubscribed.

-

The use of quota reduces the need for policies like Dominant Resource Fairness (DRF).

-

Borg has a capability system that gives special privileges to some users.

-

-

“Borg name service” (BNS) name for each task that includes the cell name, job name, and task number. Borg writes the task’s hostname and port into a consistent, highly-available file in Chubby [14] with this name, which is used by our RPC system to find the task endpoint. The BNS name also forms the basis of the task’s DNS name, so the fiftieth task in job jfoo owned by user ubar in cell cc would be reachable via 50.jfoo.ubar.cc.borg.google.com.

-

Borg also writes job size and task health information into Chubby.

-

Almost every task run under Borg contains a built-in HTTP server. Borg monitors the health-check URL and restarts tasks that do not respond promptly or return an HTTP error code.

-

Sigma provides a web-based user interface (UI) for monitoring.

-

Logs are automatically rotated to avoid running out of disk space, and preserved for a while after the task’s exit to assist with debugging.

-

If a job is not running, Borg provides a “why pending?” annotation.

-

Borg records all job submissions and task events, as well as detailed per-task resource usage information in Infrastore, a scalable read-only data store with an interactive SQL-like interface via Dremel.

-

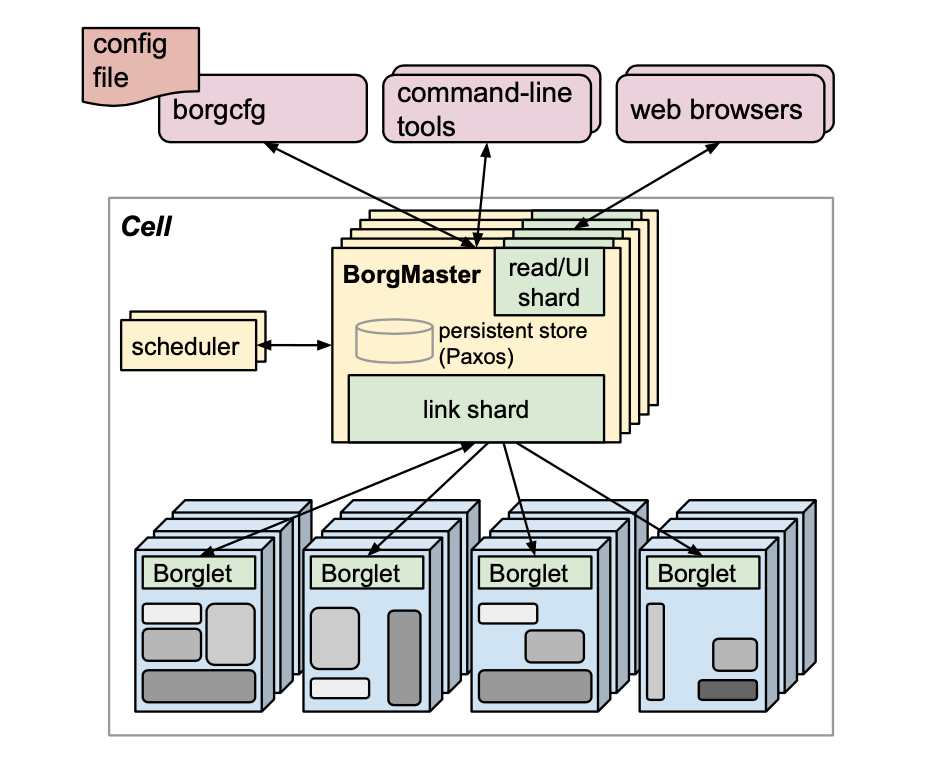

A Borg cell consists of a set of machines, a logically centralized controller called the Borgmaster, and an agent process called the Borglet that runs on each machine in a cell.

-

Borgmaster: Each cell’s Borgmaster consists of two processes: the main Borgmaster process and a separate scheduler (§3.2). The main Borgmaster process handles client RPCs that either mutate state (e.g., create job) or provide read-only access to data (e.g., lookup job). It also manages state machines for all of the objects in the system (machines, tasks, allocs, etc.), communicates with the Borglets, and offers a web UI as a backup to Sigma. Borgmaster is replicated five times.

-

Electing a master and failing-over to the new one typically takes about 10 s,.

-

The Borgmaster’s state at a point in time is called a checkpoint.

-

Fauxmaster is a high-fidelity Borgmaster simulator with stubbed-out interfaces to the Borglets. It is useful for capacity planning, as well as sanity checks.

-

-

Scheduling: When a job is submitted, the Borgmaster records it persistently in the Paxos store and adds the job’s tasks to the pending queue, which is scanned asynchronously by the scheduler. The scheduler primarily operates on tasks, not jobs with a round-robin scheme within a priority. The scheduling algorithm has two parts:

-

Feasibility checking: the scheduler finds a set of machines that meet the task’s constraints and also have enough “available” resources – which includes resources assigned to lower-priority tasks that can be evicted

-

Scoring, or determining “goodness”, mostly driven by built-in criteria such as minimizing the number and priority of preempted tasks, picking machines that already have a copy of the task’s packages, spreading tasks across power and failure domains, and, packing quality including putting a mix of high and low priority tasks onto a single machine.

-

-

Task startup latency has a median of 25s. Package installation takes about 80% of the total: one of the known bottlenecks is contention for the local disk where packages are written to. Most packages are immutable and so can be shared and cached. (This is the only form of data locality supported by the Borg scheduler.) In addition, Borg distributes packages to machines in parallel using tree and torrent-like protocols.

-

The Borglet is a local Borg agent that is present on every machine in a cell. It starts and stops tasks; restarts them if they fail; manages local resources by manipulating OS kernel settings; rolls over debug logs; and reports the state of the machine to the Borgmaster and other monitoring systems.

-

The Borgmaster polls each Borglet every few seconds to retrieve the machine’s current state and send it any outstanding requests. This gives Borgmaster control over the rate of communication, avoids the need for an explicit flow control mechanism, and prevents recovery storms.

-

For performance scalability, each Borgmaster replica runs a stateless link shard to handle the communication with some of the Borglets.

-

For resiliency, the Borglet always reports its full state,.

-

A Borglet continues normal operation even if it loses contact with the Borgmaster, so currently-running tasks and services stay up even if all Borgmaster replicas fail.

-

-

Scalability: A single Borgmaster can manage many thousands of machines in a cell, and several cells have arrival rates above 10000 tasks per minute. A busy Borgmaster uses 10–14 CPU cores and up to 50 GiB RAM.

-

To handle larger cells, they split the scheduler into a separate process so it could operate in parallel with the other Borgmaster functions that are replicated for failure tolerance.

-

To improve response times, they added separate threads to talk to the Borglets and respond to read-only RPCs.

-

Several things make the Borg scheduler more scalable: Score caching, Equivalence classes, and Relaxed randomization. Borg only does feasibility and scoring for one task per equivalence class – a group of tasks with identical requirements. Scheduler examines machines in a random order until it has found “enough” feasible machines to score, and then selects the best within that set. Scheduling a cell’s entire workload from scratch typically took a few hundred seconds, but did not finish after more than 3 days when the these three techniques were disabled.

-

Availability

Borgmaster uses a combination of techniques that enable it to achieve 99.99% availability in practice: replication for machine failures; admission control to avoid overload; and deploying instances using simple, low-level tools to minimize external dependencies. Each cell is independent of the others to minimize the chance of correlated operator errors and failure propagation. These goals, not scalability limitations, are the primary argument against larger cells.

Utilization

Increasing utilization by a few percentage points can save millions of dollars.To evaluate their policy choices we needed a more sophisticated metric than “average utilization”. They use cell compaction: given a workload, we found out how small a cell it could be fitted into by removing machines until the workload no longer fitted, repeatedly re-packing the workload from scratch to ensure that we didn’t get hung up on an unlucky configuration. Cell compaction provides a fair, consistent way to compare scheduling policies, and it translates directly into a cost/benefit result: better policies require fewer machines to run the same workload. Some results:

-

Segregating prod and non-prod work would need 20–30% more machines in the median cell to run our workload.

-

Sharing doesn’t drastically increase the cost of running programs. CPU slowdown is outweighed by the decrease in machines required over several different partitioning schemes, and the sharing advantages apply to all resources including memory and disk, not just CPU.

-

Borg users request CPU in units of milli-cores, and memory and disk space in bytes. Offering a set of fixed-size containers or virtual machines, although common among IaaS (infrastructure-as-a-service) providers, would not be a good match to their needs: doing so will require 30–50% more resources in the median case.

-

A job can specify a resource limit – an upper bound on the resources that each task should be granted. Borg estimates how many resources a task will use and reclaim the rest for work that can tolerate lower-quality resources, such as batch jobs. This whole process is called resource reclamation. The estimate is called the task’s reservation, and is computed by the Borgmaster every few seconds, using fine-grained usage (resource-consumption) information captured by the Borglet. About 20% of the workload runs in reclaimed resources in a median cell.

Isolation

50% of the machines run 9 or more tasks: Although sharing machines between applications increases utilization, it also requires good mechanisms to prevent tasks from interfering with one another

-

Security isolation: Linux chroot jail is the primary security isolation mechanism.

-

Performance isolation: All Borg tasks run inside a Linux cgroup-based resource container and the Borglet manipulates the container settings, giving much improved control because the OS kernel is in the loop.

-

To help with overload and overcommitment, Borg tasks have an application class or appclass. High-priority latency-sensitive tasks receive the best treatment, and are capable of temporarily starving batch tasks for several seconds at a time.

-

A second split is between compressible resources and non-compressible resources.

-

The standard Linux CPU scheduler (CFS) required substantial tuning to support both low latency and high utilization. Many of their applications use a thread-per-request model, which mitigates the effects of persistent load imbalances.

-

Related work

-

Apache Mesos splits the resource management and placement functions between a central resource manager (somewhat like Borgmaster minus its scheduler) and multiple “frameworks” such as Hadoop and Spark using an offer-based mechanism.

-

YARN, Hadoop Capacity Scheduler, Facebook’s Tupperware, Twitter's Aurora, Microsoft's Autopilot, Quincy, Cosmos, Microsoft’s Apollo, Alibaba’s Fuxi, are other notable examples of cluster management work.

-

Omega supports multiple parallel, specialized “verticals” that are each roughly equivalent to a Borgmaster minus its persistent store and link shards. Omega schedulers use optimistic concurrency control. The Omega architecture was designed to support multiple distinct workloads that have their own application-specific RPC interface, state machines, and scheduling policies. Borg offers a “one size fits all” RPC interface, state machine semantics, and scheduler policy, which have grown in size and complexity over time as a result of needing to support many disparate workloads, and scalability has not yet been a problem.

-

Kubernetes places applications in Docker containers onto multiple host nodes. It runs both on bare metal (like Borg) and on various cloud hosting providers, such as Google Compute Engine.

Lessons and Future work

This section describes how the lessons in building Borg have been leveraged in designing Kubernetes.

The bad

-

Jobs are restrictive as the only grouping mechanism for tasks: Kubernetes rejects the job notion and instead organizes its scheduling units (pods) using labels – arbitrary key/value pairs that users can attach to any object in the system. Operations in Kubernetes identify their targets by means of a label query that selects the objects that the operation should apply to.

-

One IP address per machine complicates things: Borg must schedule ports as a resource; tasks must pre-declare how many ports they need. Borglet must enforce port isolation; and the naming and RPC systems must handle ports as well as IP addresses. Every pod and service gets its own IP address, allowing developers to choose ports rather than requiring their software to adapt to the ones chosen by the infrastructure, and removes the infrastructure complexity of managing ports.

-

Optimizing for power users at the expense of casual ones: The BCL spec lists about 230 parameters. Unfortunately the richness of this API makes things harder for the “casual” user, and constrains its evolution.

The good

-

Allocs are useful: Allocs and packages allow such helper services to be developed by separate teams. The Kubernetes equivalent of an alloc is the pod, which is a resource envelope for one or more containers that are always scheduled onto the same machine and can share resources.

-

Cluster management is more than task management: Kubernetes supports naming and load balancing using the service abstraction: a service has a name and a dynamic set of pods defined by a label selector. Any container in the cluster can connect to the service using the service name. Under the covers, Kubernetes automatically load-balances connections to the service among the pods that match the label selector, and keeps track of where the pods are running as they get rescheduled over time due to failures.

-

Introspection is vital: Although it makes it harder for us to deprecate features and change internal policies that users come to rely on, it is still a win, and we’ve found no realistic alternative.

-

The master is the kernel of a distributed system. It is more of a kernel sitting at the heart of an ecosystem of services that cooperate to manage user jobs, like the primary UI (Sigma), and services for admission control, vertical and horizontal autoscaling, re-packing tasks, periodic job submission (cron), workflow management, and archiving system actions for off-line querying. Kubernetes architecture goes further: it has an API server at its core that is responsible only for processing requests and manipulating the underlying state objects. The cluster management logic is built as small, composable micro-services that are clients of this API server, such as the replication controller, which maintains the desired number of replicas of a pod in the face of failures, and the node controller, which manages the machine lifecycle.

Over the next few Saturdays, I'll be going through some of the foundational papers in Computer Science, and publishing my notes here. This is #17 in this series.